Text by Filippo Barbera

︎

October 8, 2024

Italy is a beautiful country made up of ugly places that nobody cares about. The trap of the so-called “Bellitalia” – a commodity very easily sold in a global standardized market – hides this plain fact in a sneaky and subtle way (Barbera et al. 2022). Let us start from the productive heart of Italy: the Pianura Padana.

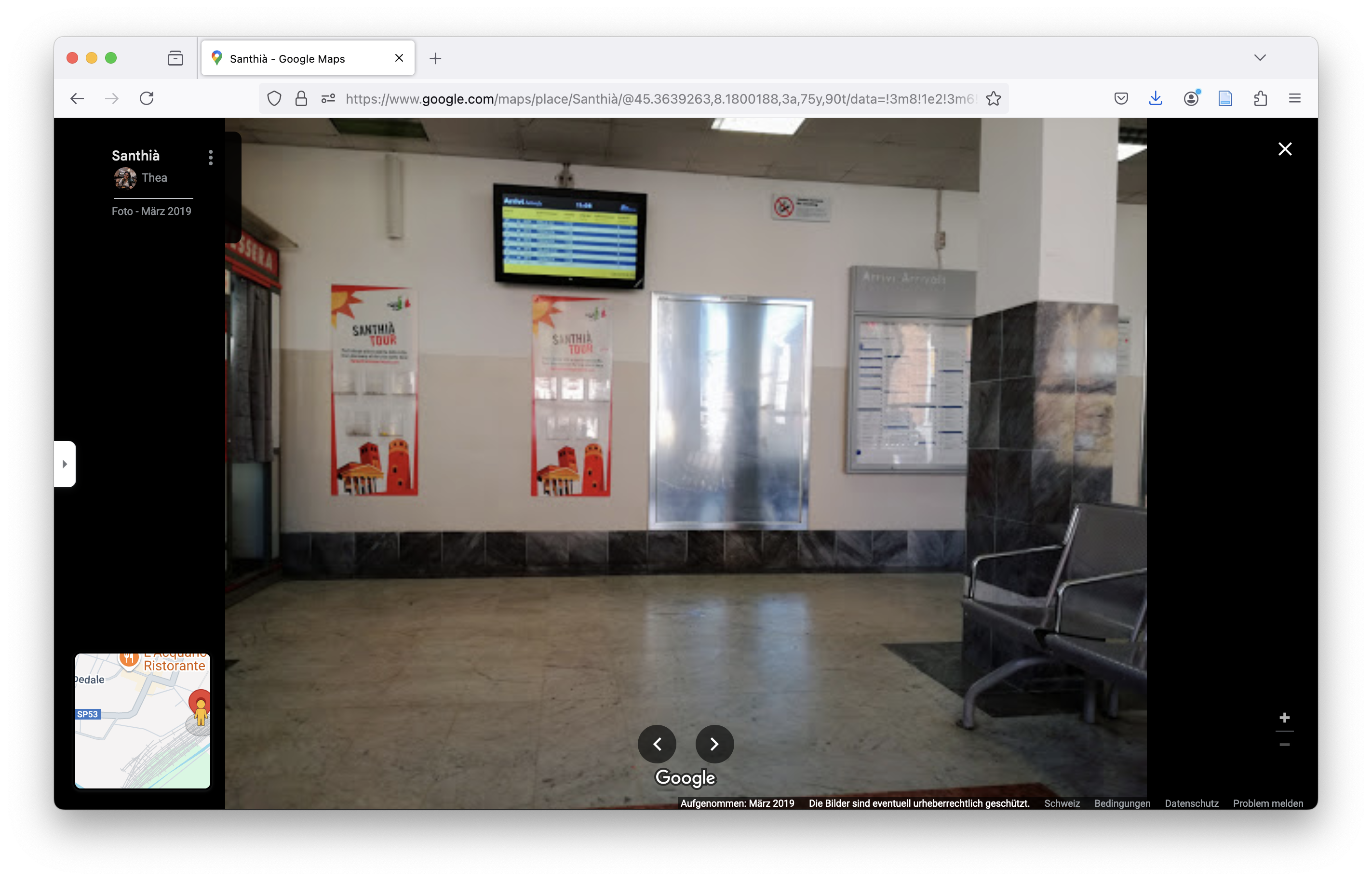

While Turin and Milan are rich in historical sites, the train connecting them daily has numerous intermediate stops from which droves of commuters, students, and, in the evening hours, prostitutes and casual workers depart and return. At these intermediate stations, line-signs have been appearing for a few years now, inviting travelers to visit the beautiful town where they are. “Here’s what you can see if you have an hour,” and then a short list, which gets longer and longer in subsequent signs, assuming you have two or three hours to spend. There is the Church of the Saint with its 19th-century organ; the palace overlooking the square, with a fresco in plain sight; sometimes a small tower.

Even the most unknown place in Italy has a cultural heritage. That is the history of the country, no more, no less. You seem to hear it, the voice of the municipal administration imploring you not to ignore that little dot on the map between Turin and Milan, to give it some of your attention, maybe then to post on social media extolling its hidden treasures: we too are part of the “most beautiful country in the world”! We too live in the reign of “Bellitalia”. The same story could be told about the train connections between Florence and Bologna, or Roma and Florence, not to mention the “endless city” between Milan and Venice.

Figure 1: VIdeo Statement by Francesco Rutelli: «please visit Italy», 2007.

Figure 1: VIdeo Statement by Francesco Rutelli: «please visit Italy», 2007.Screenshot: lastampa.it {retrieved 241008}.

The truth, to which these places and many others seem unwilling to surrender, is that they are places to which tourists have no reason to go but which nevertheless continue to chase the chimera of “touristization”. We are all tourists sneering at other tourists, as Marco D’Eramo aptly stated1. Isn’t tourism, after all, the “oil of Italy”, as Daniela Santanché – the current Ministry of Tourism – repeats tirelessly? In 2007, Francesco Rutelli – at that time Minister of Cultural Heritage and Deputy Prime Minister in the Romano Prodi II government – invited to “please visit Italy”, listing all the features of Bellitalia in 44 seconds, in a short video which many Italians still remember nowadays2.

Bellitalia is a Magazine, a TV programme, and a distorting lens through which Italians look at their country. Seeing like Bellitalia, we could say it is the looking-glass-self of Italians (as G.H. Mead would have said): the way they look at themselves through the eyes of the tourist. Bellitalia has key performative effects, and it shapes public action accordingly. For instance, Italy’s National Recovery and Resilience Plan within “Mission 1” (Digitization, Innovation, Competitiveness, Culture, and Tourism) had an investment line labeled “Village Attractiveness,” which allocated 1,020 million Euros to the rehabilitation and enhancement of historical villages (“Borghi”). It provides for selecting 21 of these villages, one for each region or autonomous province, for which 20 million are allocated. A winners-take-all logic for the lucky 21 villages. Places to reach them, you will still have to pass through several other ugly places without a positive storytelling. Or, in some cases, the road to reach them is poorly maintained or interrupted. In addition to “Borghi”, you will find abandoned hamlets with crumbling dwellings and vegetation all around, separated by torn-up sidewalks and deprived of essential services. This is because there is no Bellitalia without Bruttitalia. The hegemony of the “typical and beautiful” hamlets obscure villages and annihilates the relevance of the context that allows the village to live their mundane life, reducing its local community into a nativity scene or a re-enactment, invariably medieval, with axes, drapes, damsels, and flags.

The hegemonical role of Bellitalia has critical political implications. Bruttitalia is home to the “places that do not matter”, as Andrés Rodriguez-Pose aptly called them (Rodríguez-Pose, A. 2018). The revenge of the places that don’t matter (and what to do about it)3.Territories far away from basic services, as the metropolitan conurbations turned into dormitories, the small and medium-sized towns where tourists would not go, the France of the yellow vests, and the American Rust Belt.

Places are left on the margins of the infrastructure of citizenship and suffer from social, economic, and recognition inequalities. Places discharged by the global competition regimes and space-blind policies mainly focused on the innovative potential of the creative class living in cool&trendy cities. Places where resentment, closure, and nativism can easily fester and grow.

Figure 2:

Woodfield Street Morriston, UK (2007).

Figure 2:

Woodfield Street Morriston, UK (2007). Photo © Gareth Lovering

From Bruttitalia to Morriston

Yet an alternative exists, except that to find it – given the homogenizing force of the public narrative about Bellitalia that obscures the places that don’t matter – we have to go all the way to Wales. Researchers from the “Collective for Foundational Economy” (2018), surveyed the quality of life in anonymous townships, those where you only happen to be if your car navigator is not working4. Towns in Italy would be equivalent to “middle-size towns without particular qualities,” although they are not only or necessarily “middle-size”. In France, these are the places where the “Yellow Vests” come from: places neither central nor peripheral, median places of extended conurbations and small-to-medium cities, functionally satellites of hubs offering jobs and services5.

The case study is Morriston in Wales: 30,000 inhabitants, an industrial past, a stagnant present economy and a future yet to be defined. Putting aside the illusion of being able to seduce those from outside and thus abandoning the idea of investing scarce resources in services for phantom tourists, the ball was passed to the residents, who were interviewed about their daily lives and how they could improve. Perhaps unsurprisingly, we learn that Morriston residents don’t give a damn about the “amenities” for tourists of their small town and instead focus on the absence or malfunctioning infrastructure of daily life that they have at their disposal: access to housing, health, and social welfare facilities nearby, childcare, schools, and the local public and private transportation system. The social infrastructure of places that allows people to live a life that they feel is worth living: parks, libraries, public gathering spaces to support the “foundational liveability” of places6.

Places rich in social infrastructure where a woman can raise a child and work at the same time, while a lonely elderly person finds a place that accommodates them with dignity for their last years of life. Cities where the ordinary is at the core of public action, where the mundane matters, and where public action does not care about making the city attractive for a few sporadic tourists but is committed to equipping people’s daily lives with essential goods and services. As the residents of Morriston remind us, the well-being of a community also comes from the care for public green spaces, the maintenance of playgrounds, the creation of a basketball court where teenagers can meet, sustaining a small downtown populated with businesses that continue to exist despite the proliferation of shopping centers in the suburbs. It comes from building neighbourhood houses, community foundations, libraries, and decentralized public services. Spaces and buildings “for the people” to quote Erik Klinenberg’s work (2018).

From Bruttitalia to Morriston, the relevance of ordinary places can inform a new politics of places (Barbera 2024), preventing it from being reduced to a disguised version of trickle-down economics where inward investment in “key” sectors is expected to somehow, magically, lift local wages and living standards.

In ordinary places, the highest proportion of jobs occurs in sectors such as health, education, and social care, where wages and job quality have been eroded, and a business-led strategy will not change the picture. Ordinary places need robust social infrastructure and good jobs for ordinary people.

Ordinary places and interaction ritual chains

In recalling the effects of the fatal heat wave that swept through Chicago in 1995, the aforementioned Eric Klinenberg underlines that the difference between neighbourhoods with the highest and lowest mortality rates could be traced back to the high social segregation and spatial fragmentation of the former. In other words, a crucial difference between the two types of neighbourhoods was the gap in their social infrastructure: only some areas had shared spaces that encouraged face-to-face interaction nurtured cooperative exchanges, mutual support, trust building, reciprocity and social capital.

During the heat wave, some people were thus able to leave their unliveable over-heating flats to be hosted by other neighbourhood residents or to find refuge without consumption obligations in an air-conditioned café; in turn taking care to help their neighbours. In the neighbourhood with worn-out and fragile social infrastructure, however, this did not occur. Klinenberg thus concludes that “palaces for people” are not just physical contexts but everyday shared spaces that stimulate and enable the genesis of cooperative exchanges and mutual help.

Figure 3: Santhià train station, pianura padana 2019,

Figure 3: Santhià train station, pianura padana 2019,

Photo: Google Maps, user upload

Our cities have fewer and fewer public spaces accessible to use for whatever aim. The generally accepted minimum standard for the public space in a given urban area (defined by a minimum density of 150 inhabitants per hectare) is 45%. This is broken down into 30% for streets and sidewalks and 15% for green space7.

As of 2020, in New York, just 9% of the urban area was qualified as public open space, defined as a piece of land8. Places for the people – not to mention associative and organized settings – are even more important in this respect than sidewalks and parks. The presence of places such as community centres or neighbourhood clubs, trade unions and political and/or civic associations might even be more critical than a well-equipped courtyard of a building, a park, or a square, for they are spaces more focused on public interaction of the kind illustrated above. The spatial contraction of foundational economy goods and services such as schools, hospitals/medical services and bus/train stations widens the gap between people living in “poles” and those living in “inner areas”, contributing along with economic decline to fuel the resentment of “places that don’t matter” (Rodriguez-Pose, A. 2018).

Over time, the physical dimension of the mundane public sphere has been spatially contracted, socially segmented along class, status, age, gender, and wealth lines, and technologically digitalized.

Accordingly, the physical public sphere mirrors the parade accompanying the ending of the movie Mystic River, where Clint Eastwood denounces the descent of the American public sphere and its intermediate spaces to parade and fanfare and coloured balloons9. Or, as in Don DeLillo’s White Noise, it looks more and more like the commercialized public sphere of the places of mass consumption; where families converse about issues of public relevance by carelessly pushing shopping trolleys and greeting each other at the checkout, only to return later on to the private spaces of their homes10.

As of 2020, in New York, just 9% of the urban area was qualified as public open space, defined as a piece of land8. Places for the people – not to mention associative and organized settings – are even more important in this respect than sidewalks and parks. The presence of places such as community centres or neighbourhood clubs, trade unions and political and/or civic associations might even be more critical than a well-equipped courtyard of a building, a park, or a square, for they are spaces more focused on public interaction of the kind illustrated above. The spatial contraction of foundational economy goods and services such as schools, hospitals/medical services and bus/train stations widens the gap between people living in “poles” and those living in “inner areas”, contributing along with economic decline to fuel the resentment of “places that don’t matter” (Rodriguez-Pose, A. 2018).

Over time, the physical dimension of the mundane public sphere has been spatially contracted, socially segmented along class, status, age, gender, and wealth lines, and technologically digitalized.

Accordingly, the physical public sphere mirrors the parade accompanying the ending of the movie Mystic River, where Clint Eastwood denounces the descent of the American public sphere and its intermediate spaces to parade and fanfare and coloured balloons9. Or, as in Don DeLillo’s White Noise, it looks more and more like the commercialized public sphere of the places of mass consumption; where families converse about issues of public relevance by carelessly pushing shopping trolleys and greeting each other at the checkout, only to return later on to the private spaces of their homes10.

Films can provide alternative perspectives, though. In his movie “The Old Oak”, the British director Ken Loach tells a different story11. The story of “The Old Oak” is paradigmatic. A place once prosperous, though not rich, with an industrial economy and a proud working class, sees manufacturing plants closing down, while houses bought with so many sacrifices lose their market value, solidarity ties get easily broken, poverty and work do not exclude each other anymore, public services shrink, bankruptcy becomes ubiquitous, and the future only gets scarier. Only one meeting place remains open, the old pub in the village: “The Old Oak”. One day a group of Syrian refugees is sent to the village by the central government, abruptly and without involving the locals. The reception by the inhabitants, especially the white male ex-workers (but not only them), is not a “welcome home refugees!” Conflicts arise, and nativism runs wild. Poor against poor, race as a sign of diversity, welfare chauvinism as a legitimate allocation rule, out-group vs. in-group. A typical story of many places that do not matter, repeating over time and across countries all over the world. Votes supporting parties that promote restrictive migration policies are heavily concentrated in those areas that have experienced histories of economic decline and where the divide with places “that matter” has particularly increased over time.

Things, however, do not end there. Even in “places that do not matter”, a different story is possible. In “The Old oak”, things take a different turn when, with the owner's help of the old pub and against the regular customers, the adjacent premises – which had been closed for a long time – are restored and transformed into a shared kitchen. A great collective ritual unravels, producing social effervescence, collective identity, and a sense of mutual respect and social cohesion. Bodies “dancing” together in the same space to a familiar rhythm and with joint commitments12. The public sphere is regaining its physical depth, and the rituals of citizenship fill a community emptied of its capacity for the future with new meaning (Barbera 2024).

The story told by Ken Loach has – as in many of his movies – a social sciences backbone. In this line, Ash Amin (2023) in his great book “After Nativism: Belonging in the Age of Intolerance,” shows that the answer to nativism needs, alongside the provision of good jobs and the presence of capillary basic infrastructure, a response on the level of “symbolic capital”, capable of nourishing the needs for meaning and belonging of people living in marginalized places. A response, in other words, that also counteracts the “inequalities of recognition” and activates a different salience of local identity and its relationship to political consensus. Amin’s brilliant heuristic move is to find these new textures of meaning even in the “places that don’t matter,” precisely where the national-nativist political consensus settles more strongly. To see these seeds of hope, Amin shows, we need to focus on those “practices” of stitching and mending which create bridges of solidarity, mechanisms of sharing and exchange, capacities to aspire, hybrid identities and mobilizing assemblages, precisely in the marginalized places that propel nationalism and nativism. Through a fine-grained analysis of bodies-in-interaction in the spatial interstices of the public sphere, social practices that negate nationalist myths based on purity and nativism become apparent.

Rituals are kinds of interaction regimes that are progressive and inclusive only if they are constituted by the voice of marginalized subjects, subordinate, less powerful, or even speechless. Certainly not against their voice but also not only for their voice, with the privileged speaking “in the name” of the subalterns. In other words, the “Old Oak” shows that a shared future in mundane places can only unfold if rituals-like interaction regimes are porous, have permeable boundaries, and are intimately co-constituted by the dissonant voices of the marginalised and speechless.

Things, however, do not end there. Even in “places that do not matter”, a different story is possible. In “The Old oak”, things take a different turn when, with the owner's help of the old pub and against the regular customers, the adjacent premises – which had been closed for a long time – are restored and transformed into a shared kitchen. A great collective ritual unravels, producing social effervescence, collective identity, and a sense of mutual respect and social cohesion. Bodies “dancing” together in the same space to a familiar rhythm and with joint commitments12. The public sphere is regaining its physical depth, and the rituals of citizenship fill a community emptied of its capacity for the future with new meaning (Barbera 2024).

The story told by Ken Loach has – as in many of his movies – a social sciences backbone. In this line, Ash Amin (2023) in his great book “After Nativism: Belonging in the Age of Intolerance,” shows that the answer to nativism needs, alongside the provision of good jobs and the presence of capillary basic infrastructure, a response on the level of “symbolic capital”, capable of nourishing the needs for meaning and belonging of people living in marginalized places. A response, in other words, that also counteracts the “inequalities of recognition” and activates a different salience of local identity and its relationship to political consensus. Amin’s brilliant heuristic move is to find these new textures of meaning even in the “places that don’t matter,” precisely where the national-nativist political consensus settles more strongly. To see these seeds of hope, Amin shows, we need to focus on those “practices” of stitching and mending which create bridges of solidarity, mechanisms of sharing and exchange, capacities to aspire, hybrid identities and mobilizing assemblages, precisely in the marginalized places that propel nationalism and nativism. Through a fine-grained analysis of bodies-in-interaction in the spatial interstices of the public sphere, social practices that negate nationalist myths based on purity and nativism become apparent.

Rituals are kinds of interaction regimes that are progressive and inclusive only if they are constituted by the voice of marginalized subjects, subordinate, less powerful, or even speechless. Certainly not against their voice but also not only for their voice, with the privileged speaking “in the name” of the subalterns. In other words, the “Old Oak” shows that a shared future in mundane places can only unfold if rituals-like interaction regimes are porous, have permeable boundaries, and are intimately co-constituted by the dissonant voices of the marginalised and speechless.

About the author: Filippo Barbera is Professor of economic sociology at the CPS Department of the University of Turin and Fellow at the Collegio Carlo Alberto (Torino). He is member of the Foundational Economy Collective and of the Forum Inequalities and Diversities. Current research projects focus on the role of democratic populism in marginal areas, the regeneration of the public sphere and the analysis of foundational economy experiments in the provision of citizenship goods and services. His latest book is: Le piazza vuote, Laterza, 2024 (second edition).

Footnotes

1 http://www.meetingmediagroup.com/article/marco-d-eramo-we-are-all-tourists-sneering-at-other-tourists

2 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Lp2uDyzxP6g

3 Cambridge journal of regions, economy and society, 11(1), 189-209).

4 https://foundationaleconomy.com/2019/05/20/how-ordinary-places-work/

5 https://www.researchgate.net/publication/356843805_Geography_of_contestation_a_study_on_the_yellow_vests_movement_and_the_rise_of_populism_in_France

6 https://foundationaleconomycom.files.wordpress.com/2018/12/foundational-livability-wp-no-5-fe-collective.pdf

7 UN-Habitat (2013.) Streets as Public Spaces and Drivers of Urban Prosperity. Nairobi.

8 Source: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1243034/urban-area-share-allocated-open-public-city/

9 See https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-gf0v1M-dGs.

10 See https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wK0ni47AgRA

11 See https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fxwMfx4CjFQ

12 On joint commitments and collective agency, see Gilbert 2017.

References

Amin, A., After Nativism: Belonging in an Age of Intolerance, Polity Press, 2023

Barbera, F., Le piazze vuote, Laterza, 2024

Barbera, F. D. Cersosimo e A. De Rossi (eds.) Contro i borghi, Donzelli, 2022

Foundational Economy Collective, Foundational Economy: The Infrastructure of Everyday Life, Manchester University Press, 2018

Gilbert, M. “Joint commitment.” The Routledge handbook of collective intentionality. Routledge, 2017. 130-139.

Klinenberg, E. Palaces for the People: How Social Infrastructure Can Help Fight Inequality, Polarization, and the Decline of Civic Life, Crown, 2018

1 http://www.meetingmediagroup.com/article/marco-d-eramo-we-are-all-tourists-sneering-at-other-tourists

2 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Lp2uDyzxP6g

3 Cambridge journal of regions, economy and society, 11(1), 189-209).

4 https://foundationaleconomy.com/2019/05/20/how-ordinary-places-work/

5 https://www.researchgate.net/publication/356843805_Geography_of_contestation_a_study_on_the_yellow_vests_movement_and_the_rise_of_populism_in_France

6 https://foundationaleconomycom.files.wordpress.com/2018/12/foundational-livability-wp-no-5-fe-collective.pdf

7 UN-Habitat (2013.) Streets as Public Spaces and Drivers of Urban Prosperity. Nairobi.

8 Source: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1243034/urban-area-share-allocated-open-public-city/

9 See https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-gf0v1M-dGs.

10 See https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wK0ni47AgRA

11 See https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fxwMfx4CjFQ

12 On joint commitments and collective agency, see Gilbert 2017.

References

Amin, A., After Nativism: Belonging in an Age of Intolerance, Polity Press, 2023

Barbera, F., Le piazze vuote, Laterza, 2024

Barbera, F. D. Cersosimo e A. De Rossi (eds.) Contro i borghi, Donzelli, 2022

Foundational Economy Collective, Foundational Economy: The Infrastructure of Everyday Life, Manchester University Press, 2018

Gilbert, M. “Joint commitment.” The Routledge handbook of collective intentionality. Routledge, 2017. 130-139.

Klinenberg, E. Palaces for the People: How Social Infrastructure Can Help Fight Inequality, Polarization, and the Decline of Civic Life, Crown, 2018

Figure 4: Filmstill – Ken Loach: «The Old Oak», 2023

Figure 4: Filmstill – Ken Loach: «The Old Oak», 2023