Text by Alice Iacobone

Photographs provided by Archivio Penone

Translation from the Italian by the author

︎

October 1, 2024

Giuseppe Penone’s artworks appear as bodies whose organic growth combines with artificial construction. A twofold logic of development underlies his art: on the one hand, there is the temporal development of forms, development as growth and composition; on the other hand, there is a spatial development of the forms themselves, in the sense that they tend to unfurl as a topological unfolding of a point-like element, gathered or wrapped upon itself.

These two aspects, the temporal and the spatial, are operationally inseparable; however, it is possible to draw some distinctions for the sake of analysis. Indeed, if in the first case the development refers to the temporality of the form (understood as forma formans) and of sculpture (as sculptura sculpens), in the second case the development refers to the possibility of mapping bodies1. Penone’s works open up to an anatomical dimension of art, which, in the same gesture, also turns into a geographical dimension.

Penone works on the anatomical-geographical dimension through two different strategies. The first is a strategy that we could call “anthropometric” or “cosmomorphic”, which Penone employs when working on the human body by means of contact, imprint, or frottage. In these cases, the artist treats the body (often his own) as a landscape: anatomy becomes geography. The epidermal maps he creates are often the result of shifts in scale, so that the magnification of details generates entire environments in which one can move and place oneself. The magnification does not produce a greater recognizability of the body’s particular detail but an unimaginable landscape within the body itself.

[…]

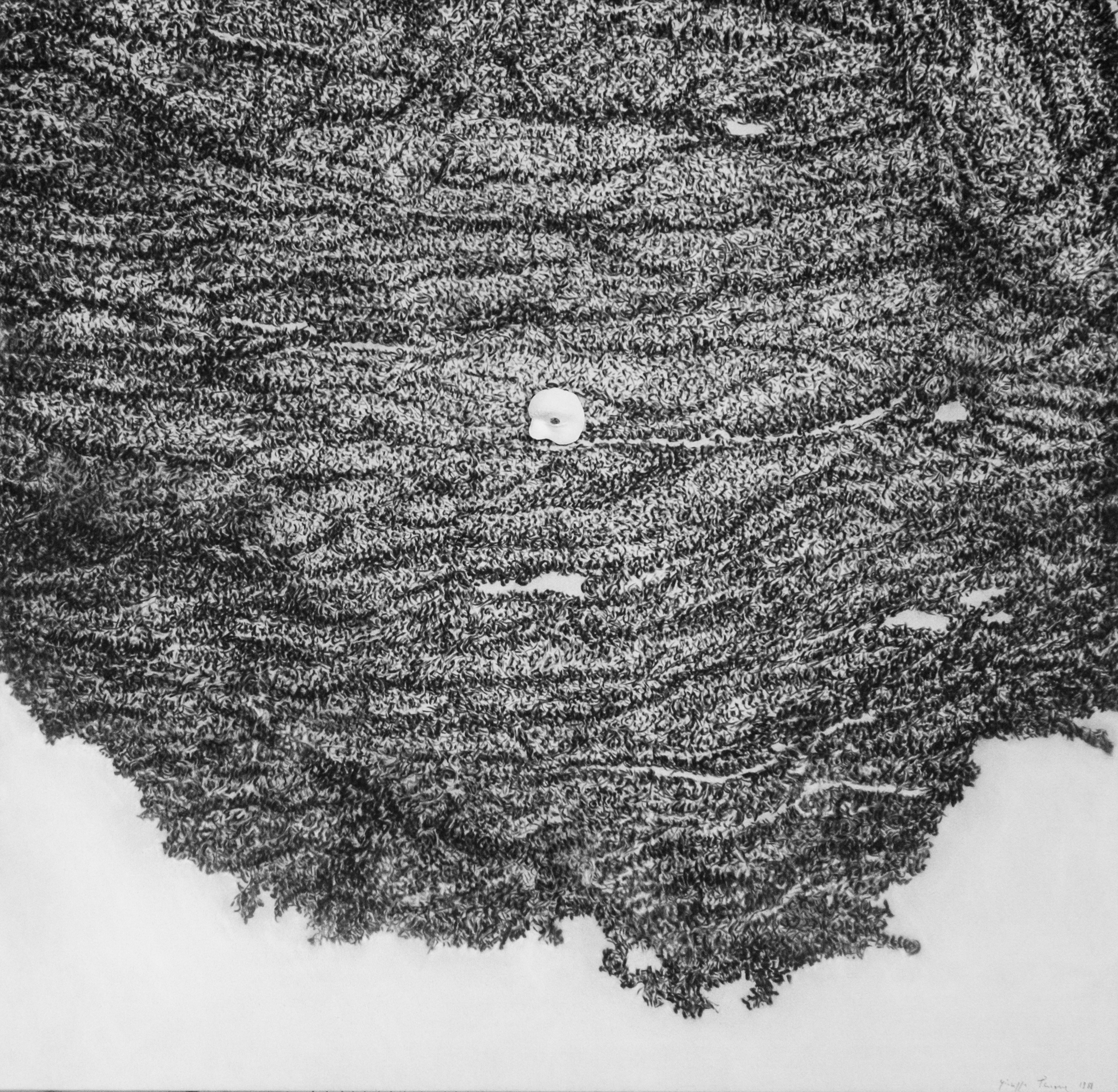

In the summer of 1977, in Garessio [the artist’s hometown, ed.], Penone dedicates himself to a large work entitled Palpebre, in which it is the epidermis of the eyelid that is revealed as a landscape. In this artwork, the topographical grid that imperceptibly traverses the artist’s eyelids is captured by imprint, thanks to resin casts. Each of the two extremely delicate casts is then inserted between two slides, and its image is projected, enlarged, onto canvas paper. On these enormous reinforced sheets, ten meters wide and two meters high, Penone traces the texture of the epidermis with charcoal [Fig. 1].

Figure 1: Palpebre (Eyelids), 1977

Figure 1: Palpebre (Eyelids), 1977

Photographic documentation in the artist’s studio

Photo © Archivio Penone

«Where there was relief on the skin», he recounts, «the resin was thinner and more transparent, where there was roughness, the greater deposit of resin reduced the transparency and outlined the landscape, the topography of the eyelid» (Penone, Elkann 2022: 184; emphasis of the author)

[Fig. 2].

Figure 2:

Palpebra (Eyelid), 1988

Figure 2:

Palpebra (Eyelid), 1988

Charcoal on felt mounted on canvas, plaster cast

Total dimensions 200 × 205 × 7 cm

Photo © Archivio Penone

This strategy – using the imprint to convert various areas of the body into as many geographical locations – was explored more radically during the 1990s when Penone moved from recording the epidermal surface to what he rightly called an «extreme frottage» (Penone 1994: 7): the frottage of the internal surface of the skull.

This procedure is put into practice in works such as Suture (1990), Foglie (1990), Paesaggio del cervello (1991). The idea of a body landscape returns explicitly; except that this landscape, unlike the epidermal geographies, is also the place where thought is materially located.

In all these cases, the anthropometric artwork results in what Penone himself does not hesitate to define as «a sort of landscape», in which the different elements of the human body are transfigured, becoming as many natural elements – «grass, leaves, roots, soil, stones» (Penone, Elkann 2022: 185; emphasis of the author). However, the shift from anatomy to geography should not be confused with a mere metaphorical operation. From the cranial bones to the leaves, from the eyelids to the landscapes, the transition does not occur through metaphor, but rather, materially, by imprint, by means of «topical conversions» (Didi-Huberman 2016: 78; emphasis in the original).

Alongside the anthropometric or cosmomorphic strategy, Penone explores the reversibility between geography and anatomy of art also according to another modality. It is the second strategy, which one could call “anthropomorphic”. Penone does not limit himself to converting the body into a landscape, but, with some works, he also shows us the landscape as a body. It is not a matter of projecting the human onto nature; it is rather a matter of finding unexpected affinities between the human and the environment, of identifying secret relationships that traverse reality and connect seemingly different elements. This is the case with the analogical relationship between the block of marble and the human body, both crossed, in different ways, by a network of veins. «I believe that in almost all languages the designs of inclusions in stones are called veins, like the blood system of our body» (Penone, Elkann 2022: 237), the artist observes. Just as the trees brought to light in the beams [the reference is to Penone’s debarked trees, ed.], flesh is exhumed in marble, according to an analogical reversibility between one and the other. Thus, visiting the quarries from which the stone is extracted, the artist observes that «the wound of a quarry reveals and makes evident to us the life of the mountain» (Penone, Elkann 2022: 64).

From these insights and experiences will derive various artworks: first of all, a series started in 1992, Anatomie [Fig. 3, in the foreground; Fig. 4].

Figure 3: In the foreground Anatomia (Anatomy), 1994,

Figure 3: In the foreground Anatomia (Anatomy), 1994, in the background Pelle di marmo e spine d’acacia (Marble Skin and Acacia Thorns), 2001

Installation view Shawinigan 2005

Photo © Archivio Penone

Here, Penone treats some blocks of marble by maintaining the geometric structure of the extracted block on some sides and by carving the mineral and bringing out its internal veins on the others. Later on, starting in 2000, series such as Pelle di marmo and Pelle del monte (2012) repeat the same operation. With these works Penone returns to the gesture of statuary, which drew the human figure from the blocks of Carrara marble, and radically inverts its meaning: here, the artist does not use the stone to represent the human, but to highlight the most intimate affinity between mineral life and human life on the basis of a common anatomy. By carving the marble block as a body, Penone shows us the similarity between the channels that animate the mountain’s matter from within, inserting in it an almost vital, maritime fluidity, and the channels through which the blood of animals or the sap of plants flows. The sensitivity underlying this analogical gesture comes from afar – just think of when, not yet twenty, Penone proposed to make portraits of stones («I imagined drawing all the stones of a stream [...] with the same spirit with which I drew people’s faces», Penone, Elkann 2022: 44).

Figure 4: Anatomia (Anatomy) [detail], 1994

Figure 4: Anatomia (Anatomy) [detail], 1994

White Carrara marble, water

3 elements, total dimensions 52 × 160 ×160 cm

Photo © Archivio Penone

Next to the conversion of the body into a landscape, there is thus the conversion of the landscape into a body. The anthropomorphic strategy should not be thought of as a genealogical operation: it is not about finding in the block of marble an alleged original state of the material, its “more authentic” quality that would bring it back to the human; Penone’s is more properly an analogical operation, a procedure aimed at highlighting possible horizontal relationships between disparate terms and domains. Thus, Penone artistically revives a gesture forbidden by major science and explored by secluded intellectual figures, like the aforementioned Simondon, or the philosopher and essayist Roger Caillois, whose “diagonal science” animated a “generalized aesthetics” (Caillois 1962) aimed at identifying unexpected continuities between the different domains of reality. Just as Caillois goes in search of «latent complicities» and «neglected correlations» (Caillois 2003: 347) between the organic and the inorganic, Penone brings to light unusual but evident relationships, only apparently extrinsic. It is true that the access route to this plane of continuity is, first and foremost, poetic and aesthetic – in a word, epidermic. Series like Pelle di marmo, spine d’acacia (from 2001) [Fig. 3, in the background] show once again that the continuity between the mineral, the vegetable, and the human is a matter of living surface: the thorns function as skin, referring to the countless nerve endings of the human epidermis (Lancioni 2018).

In his “diagonal studies”, Caillois is also interested in the phenomenon of animal mimicry. His daring interpretation is that mimetic behaviors do not represent a survival strategy but respond to a desire to let oneself go to the material, to a temptation that the inorganic exerts on the organic. The body – the “anatomical” – feels a call from the environment – the “geographical” – which invites it to question its boundaries and, with them, its identity. At this point, anatomy and geography finally meet in a true and proper co-presence. If we have seen how Penone turns anatomy into geography (the “anthropometric” strategy) and how, conversely, he turns geography into anatomy (the “anthropomorphic” strategy), what we will examine now is how the artist is also able to juxtapose anatomy and geography while keeping them in mutual tension. The encounter between anatomy and geography, treated by Caillois in a vein that one could call “ecological” (that is, as an encounter between the organism and its environmental milieu), corresponds to what in art and image theory is the encounter between figure and ground. The issue, typically understood as a pictorial one, was plastically addressed by Penone in one of his very first works.

Almost at the conclusion of this book we return to the beginnings of the artist. Within his first series Alpi Marittime (1968), Penone realized a work with the subtitle La mia altezza, la lunghezza delle mie braccia, il mio spessore in un ruscello (My height, the length of my arms, my thickness in a stream). For this work, the young Penone produced a rectangular cement structure with the dimensions of his own body; inside the frame, on the still fresh cement, he imprinted his face, hands, and feet [Fig. 5, on the left].

In his “diagonal studies”, Caillois is also interested in the phenomenon of animal mimicry. His daring interpretation is that mimetic behaviors do not represent a survival strategy but respond to a desire to let oneself go to the material, to a temptation that the inorganic exerts on the organic. The body – the “anatomical” – feels a call from the environment – the “geographical” – which invites it to question its boundaries and, with them, its identity. At this point, anatomy and geography finally meet in a true and proper co-presence. If we have seen how Penone turns anatomy into geography (the “anthropometric” strategy) and how, conversely, he turns geography into anatomy (the “anthropomorphic” strategy), what we will examine now is how the artist is also able to juxtapose anatomy and geography while keeping them in mutual tension. The encounter between anatomy and geography, treated by Caillois in a vein that one could call “ecological” (that is, as an encounter between the organism and its environmental milieu), corresponds to what in art and image theory is the encounter between figure and ground. The issue, typically understood as a pictorial one, was plastically addressed by Penone in one of his very first works.

Almost at the conclusion of this book we return to the beginnings of the artist. Within his first series Alpi Marittime (1968), Penone realized a work with the subtitle La mia altezza, la lunghezza delle mie braccia, il mio spessore in un ruscello (My height, the length of my arms, my thickness in a stream). For this work, the young Penone produced a rectangular cement structure with the dimensions of his own body; inside the frame, on the still fresh cement, he imprinted his face, hands, and feet [Fig. 5, on the left].

Finally, the artist placed the structure in the bed of a stream, positioning it horizontally: in this way, the flow of water was imperceptibly diverted by the negative imprint of Penone’s body, and as the water flowed, it momentarily assumed the artist’s features [Fig. 5, on the right]. In this work, anatomy and geography, body and environment, figure and background meet without ever resolving into one another, setting in motion a complex interaction. To account for this interaction, we invoke one final concept, that of “shallow depth”.

The expression “shallow depth” [in French “profondeur maigre”, literally “thin” or “skinny depth”], appears in the aesthetics of Gilles Deleuze, who uses it to conceptualize the relationships between figure and ground in painting (Deleuze 1981a; 2003: 136-138, 143-149). Such a superficial depth would be a subtle and unstable liminal dimension that separates and connects foreground and background, figure and ground, making the relationship between the two levels dynamic and intense, and placing the form in a state of becoming. It is a way of escaping the alternative between the dissolution of the difference between figure and background, on the one hand, and the perspectival treatment of depth, on the other (where the problem of linear perspective is that it fits figure and background into a visual-symbolic grid that stabilizes them). Shallow depth qualifies as a dynamic «intermediate zone» (Blümle 2017: 37) open between the two planes, a space where the form falls and rises, set in a constant becoming. In this sense, with Alpi Marittime – La mia altezza, la lunghezza delle mie braccia, il mio spessore in un ruscello Penone stages a non-pictorial, but rather sculptural, shallow depth, as he accentuates the relational, dynamic, and becoming dimension that connects the “figure” of his imprints to the “ground” of the stream, the anatomy of his own body to the geography of the Maritime Alps.

The role of becoming is thematized by Penone as he narrates the experience of creating this artwork:

The space of the relationship between body and environment is brought to attention and “stretched” in experience and perception. It is by “feeling” the intermediate zone, the point of contact, the «entre-deux» (Deleuze 1981b: 127, 129) space (that is, the shallow depth itself) that, according to Penone, the plastic gesture of sculpture is realized. The liminal zone and the space of becoming thus find their place within an aesthetics of the imprint, in the terms suggested by Penone’s practice2.

The concept of profondeur maigre seems pertinent to this work of “hydric” sculpture for other reasons as well. The expression, it should be noted, refers not only to the anatomical dimension (the maigreur) but also to a geography of waters: the concept does not, in fact, originate in aesthetics, but in oceanography, where it is used to describe shallow seabeds or shoals. And yet the semantic shift from oceanography to aesthetics and art theory was not first made by Deleuze, but by Clement Greenberg (1976: 50), who used the expression in relation to Jackson Pollock’s drip paintings. Evoking American abstract expressionism here does not seem out of place; on the contrary, it is precisely in comparison with Pollock’s action painting that Elizabeth Mangini analyzes the stream artwork of Alpi Marittime, noting some interesting divergences in the two approaches.

Comparing the gestures of Pollock and Penone, especially in their respective photographic documentation, Mangini highlights how the former works to reinforce the sense of artistic authority and authorship, bending the material to the assertion of his own presence (a presence that is ultimately what the viewer is called upon to perceive); whereas Penone’s gesture, by contrast, presents itself as «anti-auratic» and «anti-authoritarian» (Mangini 2021: 22):

If shallow depth presents us with the values of a non-hierarchical relationality, in which it is the intermediate space that connects and separates body and environment that takes on substance, despite its intangibility, then the concept of profondeur maigre seems far more pertinent to Penone’s gesture of lying down in the stream, surrendering his form to the becoming of the watercourse, than to Pollock’s gesture, who places the canvas on the ground only to stand upright over it.

The expression “shallow depth” [in French “profondeur maigre”, literally “thin” or “skinny depth”], appears in the aesthetics of Gilles Deleuze, who uses it to conceptualize the relationships between figure and ground in painting (Deleuze 1981a; 2003: 136-138, 143-149). Such a superficial depth would be a subtle and unstable liminal dimension that separates and connects foreground and background, figure and ground, making the relationship between the two levels dynamic and intense, and placing the form in a state of becoming. It is a way of escaping the alternative between the dissolution of the difference between figure and background, on the one hand, and the perspectival treatment of depth, on the other (where the problem of linear perspective is that it fits figure and background into a visual-symbolic grid that stabilizes them). Shallow depth qualifies as a dynamic «intermediate zone» (Blümle 2017: 37) open between the two planes, a space where the form falls and rises, set in a constant becoming. In this sense, with Alpi Marittime – La mia altezza, la lunghezza delle mie braccia, il mio spessore in un ruscello Penone stages a non-pictorial, but rather sculptural, shallow depth, as he accentuates the relational, dynamic, and becoming dimension that connects the “figure” of his imprints to the “ground” of the stream, the anatomy of his own body to the geography of the Maritime Alps.

The role of becoming is thematized by Penone as he narrates the experience of creating this artwork:

To create the sculpture, it is necessary for the sculptor to lie down, to lie on the ground allowing himself to slide [...] and finally, once horizontal, to concentrate his attention and efforts on his body, which, pressed against the ground, allows him to see and feel the things of the earth against him. [...] The sculptor penetrates... and the line of the horizon approaches his eyes. When he finally feels his head light, the cold of the earth cuts him in half and makes clear and precise the point that separates the part of his body that belongs to the void of the sky from the part that belongs to the fullness of the earth. It is then that the sculpture takes place. (Penone 2009: 56)

The space of the relationship between body and environment is brought to attention and “stretched” in experience and perception. It is by “feeling” the intermediate zone, the point of contact, the «entre-deux» (Deleuze 1981b: 127, 129) space (that is, the shallow depth itself) that, according to Penone, the plastic gesture of sculpture is realized. The liminal zone and the space of becoming thus find their place within an aesthetics of the imprint, in the terms suggested by Penone’s practice2.

The concept of profondeur maigre seems pertinent to this work of “hydric” sculpture for other reasons as well. The expression, it should be noted, refers not only to the anatomical dimension (the maigreur) but also to a geography of waters: the concept does not, in fact, originate in aesthetics, but in oceanography, where it is used to describe shallow seabeds or shoals. And yet the semantic shift from oceanography to aesthetics and art theory was not first made by Deleuze, but by Clement Greenberg (1976: 50), who used the expression in relation to Jackson Pollock’s drip paintings. Evoking American abstract expressionism here does not seem out of place; on the contrary, it is precisely in comparison with Pollock’s action painting that Elizabeth Mangini analyzes the stream artwork of Alpi Marittime, noting some interesting divergences in the two approaches.

Comparing the gestures of Pollock and Penone, especially in their respective photographic documentation, Mangini highlights how the former works to reinforce the sense of artistic authority and authorship, bending the material to the assertion of his own presence (a presence that is ultimately what the viewer is called upon to perceive); whereas Penone’s gesture, by contrast, presents itself as «anti-auratic» and «anti-authoritarian» (Mangini 2021: 22):

Penone’s body is positioned coincident with the horizontal plane of Pollock’s substrate, problematizing both artistic authority over the material world and the presumed transparency of gestural abstraction. Penone does not stand erect [...] nor is he skillfully controlling the flow of liquid. Although the artist’s body – via a surrogate – affects the movement of the stream, [...] it is no different from a stone or a fallen tree branch. His body here sculpts the stream as water passes over and through the concrete obstruction, but it neither dominates the stream-bed nor diverts the water for human ends. Rather, the artist here lowers himself to the same plane as the water, the earth, and the stones. That is, his body enters into the work but does not dictate the field or the form. The horizontal “surface”, meanwhile, is not flat and submissive like Pollock’s canvas, but deep and dynamic. (Mangini 2021: 25)

If shallow depth presents us with the values of a non-hierarchical relationality, in which it is the intermediate space that connects and separates body and environment that takes on substance, despite its intangibility, then the concept of profondeur maigre seems far more pertinent to Penone’s gesture of lying down in the stream, surrendering his form to the becoming of the watercourse, than to Pollock’s gesture, who places the canvas on the ground only to stand upright over it.

This article is an excerpt from the book Per crescita di buio. Estetica e poetica di Giuseppe Penone [“Per crescita di buio”. Aesthetics and Poetics of Giuseppe Penone], Quodlibet, Macerata 2023, 176 pp., here: 128-142.

I warmly thank the artist Giuseppe Penone, his son Ruggero Penone, and the archivist Luca Spanu for their invaluable support, without which my research would have not been possible. Alice Iacobone, autumn 2024.

About the author: Alice Iacobone just earned her PhD in Philosophy, Aesthetics, from the University of Eastern Piedmont (Italy), with a dissertation titled Plasticity and Sculpture. Forms – Materials – Imprints. During her PhD, she has been a doctoral fellow at the University of Turin, Department of Philosophy, and at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Department of Art and Image History; she also spent a visiting period at École des hautes études en sciences sociales (EHESS), Paris. Her research interests include, among others, material aesthetics and material politics, environmental philosophy and future studies, contemporary art and speculative evolution.

I warmly thank the artist Giuseppe Penone, his son Ruggero Penone, and the archivist Luca Spanu for their invaluable support, without which my research would have not been possible. Alice Iacobone, autumn 2024.

About the author: Alice Iacobone just earned her PhD in Philosophy, Aesthetics, from the University of Eastern Piedmont (Italy), with a dissertation titled Plasticity and Sculpture. Forms – Materials – Imprints. During her PhD, she has been a doctoral fellow at the University of Turin, Department of Philosophy, and at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Department of Art and Image History; she also spent a visiting period at École des hautes études en sciences sociales (EHESS), Paris. Her research interests include, among others, material aesthetics and material politics, environmental philosophy and future studies, contemporary art and speculative evolution.

Footnotes

1 On how Penone’s gesture differs from techno-scientific subsumptions of bodies through mapping, see the second chapter of the book, in particular pp. 69-72.

2 For an extensive theorization of Penone’s “aesthetics of the imprint”, see the first chapter of the book, in particular pp. 36-48.

References

- Blümle, C. (2017). “Seichte Tiefe. Zum Gespenstischen in der Malerei Francis Bacons”, in U. Holl, C. Pias, B. Wolf (eds.), Gespenster des Wissens. Festschrift für Joseph Vogl, Zürich-Berlin: Diaphanes: 35-40.

Caillois, R. (1962). Esthétique généralisée, Paris: Gallimard.

Caillois, R. (2003). “A New Plea for Diagonal Science”, in Id., The Edge of Surrealism: A Roger Caillois Reader, ed. by C. Frank, Durham: Duke University Press: 343-347.

Deleuze, G. (1981a). La peinture et la question des concepts, course held at Université Paris 8 Vincennes-Saint-Denis, March – June 1981, recordings and transcriptions available online (www2.univ-paris8.fr/deleuze/rubrique.php3?id_rubrique=7). Now partially published as Sur la peinture. Cours mai-juin 1981, ed. by D. Lapoujade, Paris: Éditions de Minuit, 2023.

Deleuze, G. (1981b). Francis Bacon. Logique de la sensation, Paris: Éditions de la Différence.

Deleuze, G. (2003). Francis Bacon. The Logic of Sensation, London-New York: Continuum.

Didi-Huberman, G. (2016). Being a Skull: Site, Contact, Thought, Sculpture, Minneapolis: Univocal.

Greenberg, C. (1976). “Les textes sur Pollock”, in Macula. Revue trimestrielle 2: 36-56.

Lancioni, D. (2018). “Anatomies”, booklet 8, in C. Basualdo (ed.), Giuseppe Penone. The Inner Life of Forms, New York: Gagosian-Rizzoli International Publications.

Mangini, E. (2021). Seeing Through Closed Eyelids: Giuseppe Penone and the Nature of Sculpture, Toronto-Buffalo-London: University of Toronto Press.

Penone, G. (1994). Giuseppe Penone. L’image du toucher, exhibition catalogue (Amiens, Fonds régional d’art contemporain de Picardie, October 1 – December 11, 1994), Amiens: FRAC Picardie.

Penone, G. (2009). Scritti 1968-2008, ed. by G. Maraniello, J. Watkins, companion book to the exhibitions (Bologna, MAMbo, September 25 – December 8, 2008; Birmingham, IKON Gallery, June 3 – July 19, 2009).

Penone, G., Elkann, A. (2022). 474 risposte, Milano: Bompiani.

1 On how Penone’s gesture differs from techno-scientific subsumptions of bodies through mapping, see the second chapter of the book, in particular pp. 69-72.

2 For an extensive theorization of Penone’s “aesthetics of the imprint”, see the first chapter of the book, in particular pp. 36-48.

References

- Blümle, C. (2017). “Seichte Tiefe. Zum Gespenstischen in der Malerei Francis Bacons”, in U. Holl, C. Pias, B. Wolf (eds.), Gespenster des Wissens. Festschrift für Joseph Vogl, Zürich-Berlin: Diaphanes: 35-40.

Caillois, R. (1962). Esthétique généralisée, Paris: Gallimard.

Caillois, R. (2003). “A New Plea for Diagonal Science”, in Id., The Edge of Surrealism: A Roger Caillois Reader, ed. by C. Frank, Durham: Duke University Press: 343-347.

Deleuze, G. (1981a). La peinture et la question des concepts, course held at Université Paris 8 Vincennes-Saint-Denis, March – June 1981, recordings and transcriptions available online (www2.univ-paris8.fr/deleuze/rubrique.php3?id_rubrique=7). Now partially published as Sur la peinture. Cours mai-juin 1981, ed. by D. Lapoujade, Paris: Éditions de Minuit, 2023.

Deleuze, G. (1981b). Francis Bacon. Logique de la sensation, Paris: Éditions de la Différence.

Deleuze, G. (2003). Francis Bacon. The Logic of Sensation, London-New York: Continuum.

Didi-Huberman, G. (2016). Being a Skull: Site, Contact, Thought, Sculpture, Minneapolis: Univocal.

Greenberg, C. (1976). “Les textes sur Pollock”, in Macula. Revue trimestrielle 2: 36-56.

Lancioni, D. (2018). “Anatomies”, booklet 8, in C. Basualdo (ed.), Giuseppe Penone. The Inner Life of Forms, New York: Gagosian-Rizzoli International Publications.

Mangini, E. (2021). Seeing Through Closed Eyelids: Giuseppe Penone and the Nature of Sculpture, Toronto-Buffalo-London: University of Toronto Press.

Penone, G. (1994). Giuseppe Penone. L’image du toucher, exhibition catalogue (Amiens, Fonds régional d’art contemporain de Picardie, October 1 – December 11, 1994), Amiens: FRAC Picardie.

Penone, G. (2009). Scritti 1968-2008, ed. by G. Maraniello, J. Watkins, companion book to the exhibitions (Bologna, MAMbo, September 25 – December 8, 2008; Birmingham, IKON Gallery, June 3 – July 19, 2009).

Penone, G., Elkann, A. (2022). 474 risposte, Milano: Bompiani.

Figure 5: Alpi Marittime. La mia altezza, la lunghezza delle mie braccia, il mio spessore in un ruscello

Figure 5: Alpi Marittime. La mia altezza, la lunghezza delle mie braccia, il mio spessore in un ruscello