Text by David gé Bartoli, Sophie Gosselin, Marin Schaffner and Stefan Kristensen

Translation by Emiliano Guaraldo

Drawings by Clémence Mathieu

︎

September 16, 2024

From April 20 to 23, 2024, we convened in Geneva to discuss the establishment of a Diplomatic Council of River Basins. Designed as a bioregional counterpart to the United Nations, this emerging institution has the ambition to shape an alternative approach to the geopolitics of the Earth, grounded in territories that are undergoing significant transformations. Below are its primary political and theoretical orientations..

Considering that:

● glaciers are melting in Spring, disrupting the water cycle and causing sea levels to rise,

● rivers and streams are increasingly endowed with legal personhood worldwide,

● Switzerland hosts the sources of four major European river basins: the Rhône, the Rhine, the Inn (a tributary of the Danube), and the Ticino (a tributary of the Po),

● Geneva, as an international diplomatic center, remains largely anthropocentric and insufficiently responsive to ongoing ecological upheavals,

We propose to create a Diplomatic Council of River Basins on the shores of Lake Geneva. This prospective institution will amplify the voices of various entities—mountains, waterways, forests, animals, plants, and others—that have long been marginalized, yet are essential to the life and health of river basins, which are now under threat.

· · ·

There is no doubt: climate change is transforming the face of the Earth. This sweeping upheaval compels us to rethink how we inhabit and inscribe ourselves into mutating territories. Water, essential to life on Earth, becomes the focal element around which a new politics of vital interdependencies is being recomposed.

The political institutions inherited from modernity seem increasingly unable to address the surge of socio-ecological and health catastrophes – on the contrary, they exacerbate them through extractive and productivist economic approaches that deepen social and environmental injustices.

In response, communities worldwide are mobilizing to protect and care for their rivers, forests, and mountains. They are demanding the recognition of rights to the ecosystems in which they live, affirm their connection to the diverse beings that inhabit their territories of life, and build networks of solidarity to support the most vulnerable, both human and non-human. Many of these initiatives originate in the Global South. As inhabitants of the modern West, we are faced with the imperialist frameworks that have driven these disruptions and we must confront the need to decolonize our ways of inhabiting the world. From these transformative perspectives, we seek to reimagine diplomatic issues through an ecological, and thus terrestrial, lens.

As a result of the Juntas de Buen Gobierno in the Zapatista mountains of Mexico, the experiments in federated ecological communes in Rojava (Kurdistan), the massive farmers’ protests in India, the desert re-greening practices in the Sahel, the recognition of rivers (such as the Whanganui in New Zealand and Atrato in Colombia) and lagoons (such as Mar Menor in Spain) as legal entities, the networks of permaculture gardens in Australia—in short, as a result of all the inhabiting, re-inhabiting, peasant and indigenous initiatives of the world, we state that current diplomatic frameworks no longer serve us, they appear to us as both bellicose and obsolete.

Close to us, and echoing these ways of composing with and caring for our territories of life, various initiatives in Switzerland and France have recently sought institutional translations to various inhabiting dynamics: the Limousin Mountain Syndicate, the Drôme Biovalley, the assemblies of the ZAD at Notre-Dame-des-Landes, the communal ecology zones of Lentillères in Dijon, the Parliament of the Loire, the Popular Assembly of the Rhône, and many others.

These instituent initiatives are increasingly breaking free from the confines of administrative boundaries imposed by modern nation-states, aligning instead with the natural cycles of water and land that sustain diverse forms of life. In doing so, they contribute to the rise of a new political geography attuned to the problems of a disrupted planet—what we might call a geopolitics of river basins.

A river basin is the region encompassed by a river and all its tributaries. It is a whole world that sustains countless human and non-human lives. Following the dividing lines that surround a river basin, every drop of water flows inevitably toward the sea, making river basins the Earth’s veins1.

Amid these new instituent dynamics, there is a growing need to imagine European spaces of encounter and dialogue that can accompany the recomposition of emerging political territories. The research-creation launched by this Diplomatic Council of River Basins seeks to address this need. In close proximity to the United Nations in Geneva, the Diplomatic Council aims to define the institutional frameworks for a geopolitics of the Earth that can meet the challenges of mutating territories. Geneva, in this context, serves as both a nerve center and a meeting point. It is a nerve center due to its location at the heart of a natural continental “water tower,” its position on the shores of the largest Alpine lake, its role as an international hub for anthropocentric diplomacy, and its future as the site of the Circular Collider, one of Europe’s largest industrial projects. But it is also a meeting point – a cross-border region undergoing redefinition, where, with a telluric movement, the snow-free Alps slowly rise.

A river basin is the region encompassed by a river and all its tributaries. It is a whole world that sustains countless human and non-human lives. Following the dividing lines that surround a river basin, every drop of water flows inevitably toward the sea, making river basins the Earth’s veins1.

Amid these new instituent dynamics, there is a growing need to imagine European spaces of encounter and dialogue that can accompany the recomposition of emerging political territories. The research-creation launched by this Diplomatic Council of River Basins seeks to address this need. In close proximity to the United Nations in Geneva, the Diplomatic Council aims to define the institutional frameworks for a geopolitics of the Earth that can meet the challenges of mutating territories. Geneva, in this context, serves as both a nerve center and a meeting point. It is a nerve center due to its location at the heart of a natural continental “water tower,” its position on the shores of the largest Alpine lake, its role as an international hub for anthropocentric diplomacy, and its future as the site of the Circular Collider, one of Europe’s largest industrial projects. But it is also a meeting point – a cross-border region undergoing redefinition, where, with a telluric movement, the snow-free Alps slowly rise.

1. Starting from re-inhabiting communities: taking care of environments of life

Despite the global spread of extractive and neoliberal capitalism, “re-inhabitant” communities continue to emerge and thrive within the gaps of an increasingly uniform, monocultural world. The concept of re-inhabitation originates from the bioregionalist movement. “Everywhere, communities of people are emerging, attempting new ways of living on and with the Earth,”2 wrote environmental activist Peter Berg and biologist Raymond Dasmann in their influential 1976 article, Re-inhabiting California.

In recent decades, France has seen various examples of such efforts. Among them are the ZAD of Notre-Dame-des-Landes, with its well-known slogan “We are nature defending itself,” the Syndicat de la Montagne Limousin, an autonomous, multicultural residents’ union, and the Comité Loire Vivante (a coalition of groups that united in the late 1980s to oppose the construction of four large dams in the Loire River basin), a movement now extended through the Parliament of the Loire. Another notable example is the Biovallée du Drôme, which promotes regenerative agricultural practices to sustain and care for the land.

These different dynamics of inhabitation (and institution) put different strategies into practice: a defense of the Earth’s common goods, rights of nature, permacultural practices, etc. They have in common the rethinking of territorialities (attachments to places) starting from the ways of living and the alliances between humans and non-humans. The tasks are multiple: rediscovering the link with the land, combining ecological justice and social justice, caring for interdependencies by and through re-inhabiting practices ... In all cases, a redefinition of the territory is at stake.

In these emerging perspectives, territory is no longer a portion of space managed by an administration, but a dynamic network that brings together a plurality of ways of life. According to this ecocentric (and no longer anthropocentric) view, the permanent metamorphosis of our living environments calls for a fundamental revaluation of the ethical principles underlying our political decisions. As Peter Berg expressed in 1986: “The place where you live is alive, and you are part of its life. What then are your obligations in this regard, what is your responsibility to the place that welcomes and nourishes you?”3 Building on this bioregionalist vision, our question becomes: how can we make people from and with living environments? In this perspective, peoples are not pre-constituted entities, they are constituted in and through the alliances they weave with the different ways of life that make up the fabric of a complex and changing territory, the fabric of a “body-territory.”4

1.2. Earth peoples

From the territories of life – and therefore from the “bodies-territories”5 – emerges the possibility of an expanded, more-than-human “we,” which redraws the boundaries (always open and welcoming) of our communities of life and the lines of separation and passage between humans and non-humans, and which gives birth to ways of making people that no longer respond to the anthropocentric and nationalist coordinates inherited from modernity: river-people, mountain-people, forest-people, coastal-people.6 In most cases, water has proven to be the link that enables new connections between a “territory” and a way of making “people.”

“Like the cardiovascular network that distributes oxygen and nutrients essential for life to our vital organs, the river network is the vehicle that transports living beings, irrigates the land and crosses terrestrial bodies to connect them to each other within plural and living bodies-territories: from the glacier to the river, from the spring to the estuary, from the land to the sea, from the clouds to the forests, from the rain to the aquifers... Water connects bodies, territories and continents. It draws borders other than those arbitrarily established by modern nation-states: zones of encounter and transition, from which it is possible to relearn how to build a community and create new alliances between humans and non-humans.”7

It is from the river basins that we wish to consider both the ecological ways of life that we defend and, by extension, their institutional translations.

1.3 Watershed institutions

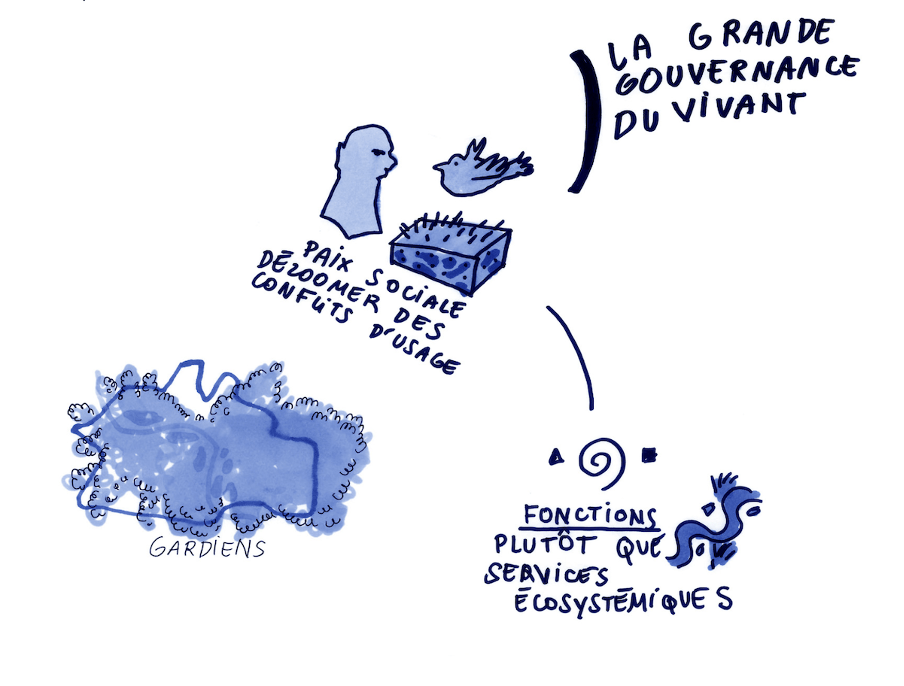

What institutions can terrestrial peoples give birth to?

These re-inhabiting dynamics invite us to question the meaning of the notion of “institution.” Most political and social institutions are inherited, and reproduce anthropocentric and patriarchal principles of domination – based on forms of racial and gender domination and reducing natural beings to mere resources. How, then, can we expect such institutions to adapt to these fundamentally different ways of inhabiting and living?

What interests us here are not fixed, instituted dispositifs, but the instituting processes – those that would be capable of accompanying the permanent metamorphoses of a territory, the inscription in time of the practices of community inhabitants, and the ways of making people to which they give birth. In other words, we consider that through such instituting dynamics, it is the territory itself that is instituted as an “Earth people.”8 Or rather, it is the alliances between humans and non-humans that should institute the territory as a political entity.

The political imaginary of the federation of river basins, so valued by the bioregionalists, can serve as a source of inspiration, inviting us to make water the primordial commons of all life, and therefore of all politics. It allows us to contemplate what could be, in all their diversity, peoples of water, capable of shaping hydroworlds: “a set of ecological continuities, always more than human, within which we are immersed, which we make, and which make us at every moment, everywhere on the planet.”9 A set of ancestral and existential relations of interdependence and care between communities of life and aquatic environments. According to the idea that these aquatic worlds are at the same time within us, between us, and beyond us. Making people from these changing territorialities that are the river basins means rethinking geopolitical issues from their very foundations.

2. Towards water cycle policies: redrawing our interdependencies

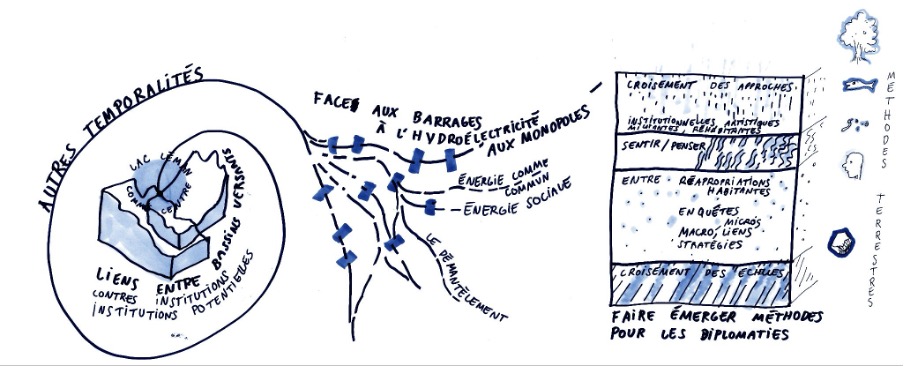

At the crossroads of the three preceding notions (territories, peoples, institutions), water policies appear as a particularly interesting touchstone for rethinking the general equation of disaster.

Since 1964 and the creation of the Water Agencies in France, water resource management at the level of river basins has become the norm throughout Europe. But words matter: “management” and “resource” are deeply problematic terms within European water policies. The care of resources takes place from an anthropocentric standpoint: river basins serve human uses, and are managed to continue serving them, without deteriorating too much. This is a kind of “reasoned” exploitation, which becomes less and less viable as the climate crisis worsens. Water agencies are a magnificent invention on paper, but they are caught in the web of a systemic way of thinking, which favours utilitarianism and resourcism, as well as the representation of interests and their power games in the form of lobbying.

2.1 Re-inhabiting water cycles

Water circulation (surface, underground and atmospheric) operates through multiple cycles. Faced with the increase in floods and droughts, it seems that respect for these cycles is what must guide us now. How can we orient ourselves towards “water cycle policies?”10 The first answer is the recognition of the importance of these cycles within our institutions, as they sustain all the dynamics of life, and are disrupted by ecological upheaval. The second, closely related, is the extension of democratic relationships beyond the human. This is what the Indian eco-feminist activist Vandana Shiva has called “Earth democracy:” modes of organization that are respectful of all the facets of our great earthly family.11 What we desperately need are more-than-human commons, biocultural commons: that is, shared living environments within which human modes of organization allow all other nonhumans (and life cycles more broadly) to develop as freely as possible.

2.2 Permaculture and the politics of the commons

Permaculture is rooted in the observation and imitation of natural cycles and offers an inspiring ethical framework. Founded in the 1970s in Australia, and now spreading across the planet, permaculture redefines the notion of “commons” from a post-industrial and sustainable perspective: care of places and energy consumption reduction. Permaculture rethinks the place of humans within their environments and re-inscribes agricultural practices within the horizon of a general ecological culture based on care. Conceiving environments that feed us without causing harm to them, is an ethical orientation that reconnects with ancient indigenous and peasant practices, a promising way to stop the disaster. From its inception, permaculture has drawn explicitly on two fundamental approaches to the reformulation of cohabitation: communalism and bioregionalism. The former with its emphasis on autonomous confederated ecological communes, and the latter through its river basin councils, are crucial to reimagining the vital commons that is water and thus forging a new “direct water democracy.”12 The notion of subsistence needs to be placed again at the center of our daily lives. Because there is no true ecological subsistence without policies of cycles: the seasons, the lunar phases, the waters, the soil’s life processes... there are fundamental rights – those of subsistence – that the mercantile and extractive society is systematically denying us. Reclaiming these rights is essential – the term “reclaim,” dear to ecofeminists, means at the same time to claim, reappropriate, and repair. The creation of a Diplomatic Council of River Basins is one step towards this goal.

2.3 Water to regenerate our interdependencies

A persuasive concrete example of regeneration is the story of Hatakeyama Shigeatsu, a Japanese oyster farmer who, faced with the pollution of Kesennuma Bay and the massive death of his oysters, initiated a large-scale tree-replanting movement with the villages upstream, along his small coastal river. The water – purified naturally, but thanks to the effort of the local human communities – enabled the oysters to thrive once again. Hatakeyama Shigeatsu’s fascinating account of this experience, entitled The Sea Loving Forest,13 offers a powerful and simple reminder of our urgent task: to safeguard the functionality and continuity of natural cycles. The pursuit of “water cycle policies” is a method – at once artistic, political, and scientific – to question our engagement with the environment. At its core, it reflects a desire to create and uphold a true ecological hospitality on a planet increasingly disrupted by environmental change.

3. Earth rights and democracy of the living: for an interworld of water people

These ways of inhabiting living environments and caring for the living find an important source of inspiration in the resistance and persistence of the peoples of the South, in particular indigenous peoples who, for centuries, have sought to defend their lands and conditions of subsistence against the logic of colonial hoarding and destruction.

3.1 The rights of Mother Earth

In the Latin American context, indigenous struggles have taken the lead in place of a weaning workers’ movement, redefining both the meaning and scope of political conflict. To confront socio-economic inequalities and domination, we must also question all other forms of domination, including patriarchal and colonial power rooted in cosmocide and ecocide,14 in the destruction of the plurality of ways of making worlds and living environments. The specificity of these struggles is that they combine social and ecological justice, as it is evident in the various Latin American declarations recognizing the rights of Mother Earth (or Pachamama): “Just as human beings enjoy human rights, all other beings have rights specific to their species or type, and adapted to the role and function they exercise within the communities in which they exist.”15

The comparison of the Earth to a mother reflects its role as the generative force behind all forms of life. The goal is to create the conditions for regenerating the cycles of life, by caring for the “indivisible community of life composed of interdependent beings intimately linked to each other by a common destiny”.16 This approach is put into practice by “buen vivir,” Footonote 17 a concept describing a communal way of life based on a holistic approach to the relations between humans and non-humans.

Permaculture is rooted in the observation and imitation of natural cycles and offers an inspiring ethical framework. Founded in the 1970s in Australia, and now spreading across the planet, permaculture redefines the notion of “commons” from a post-industrial and sustainable perspective: care of places and energy consumption reduction. Permaculture rethinks the place of humans within their environments and re-inscribes agricultural practices within the horizon of a general ecological culture based on care. Conceiving environments that feed us without causing harm to them, is an ethical orientation that reconnects with ancient indigenous and peasant practices, a promising way to stop the disaster. From its inception, permaculture has drawn explicitly on two fundamental approaches to the reformulation of cohabitation: communalism and bioregionalism. The former with its emphasis on autonomous confederated ecological communes, and the latter through its river basin councils, are crucial to reimagining the vital commons that is water and thus forging a new “direct water democracy.”12 The notion of subsistence needs to be placed again at the center of our daily lives. Because there is no true ecological subsistence without policies of cycles: the seasons, the lunar phases, the waters, the soil’s life processes... there are fundamental rights – those of subsistence – that the mercantile and extractive society is systematically denying us. Reclaiming these rights is essential – the term “reclaim,” dear to ecofeminists, means at the same time to claim, reappropriate, and repair. The creation of a Diplomatic Council of River Basins is one step towards this goal.

2.3 Water to regenerate our interdependencies

A persuasive concrete example of regeneration is the story of Hatakeyama Shigeatsu, a Japanese oyster farmer who, faced with the pollution of Kesennuma Bay and the massive death of his oysters, initiated a large-scale tree-replanting movement with the villages upstream, along his small coastal river. The water – purified naturally, but thanks to the effort of the local human communities – enabled the oysters to thrive once again. Hatakeyama Shigeatsu’s fascinating account of this experience, entitled The Sea Loving Forest,13 offers a powerful and simple reminder of our urgent task: to safeguard the functionality and continuity of natural cycles. The pursuit of “water cycle policies” is a method – at once artistic, political, and scientific – to question our engagement with the environment. At its core, it reflects a desire to create and uphold a true ecological hospitality on a planet increasingly disrupted by environmental change.

3. Earth rights and democracy of the living: for an interworld of water people

These ways of inhabiting living environments and caring for the living find an important source of inspiration in the resistance and persistence of the peoples of the South, in particular indigenous peoples who, for centuries, have sought to defend their lands and conditions of subsistence against the logic of colonial hoarding and destruction.

3.1 The rights of Mother Earth

In the Latin American context, indigenous struggles have taken the lead in place of a weaning workers’ movement, redefining both the meaning and scope of political conflict. To confront socio-economic inequalities and domination, we must also question all other forms of domination, including patriarchal and colonial power rooted in cosmocide and ecocide,14 in the destruction of the plurality of ways of making worlds and living environments. The specificity of these struggles is that they combine social and ecological justice, as it is evident in the various Latin American declarations recognizing the rights of Mother Earth (or Pachamama): “Just as human beings enjoy human rights, all other beings have rights specific to their species or type, and adapted to the role and function they exercise within the communities in which they exist.”15

The comparison of the Earth to a mother reflects its role as the generative force behind all forms of life. The goal is to create the conditions for regenerating the cycles of life, by caring for the “indivisible community of life composed of interdependent beings intimately linked to each other by a common destiny”.16 This approach is put into practice by “buen vivir,” Footonote 17 a concept describing a communal way of life based on a holistic approach to the relations between humans and non-humans.

3.2 River institutions and river narratives

Indigenous struggles and declarations of the rights of Mother Earth in Ecuador (2008) and Bolivia (2010) have sparked significant institutional innovations across continents: in Colombia, India, New Caledonia, New Zealand, Canada. In Europe, between 2019-2021, several initiatives emerged: in the Loire, the Rhône, and the Tavignanu, local communities have mobilized to demand legal recognition of the rights of their rivers and the ecosystems they inhabit.

In October 2023, the Mar Menor lagoon in Murcia, Spain, became the subject of a popular law, validated by the Spanish Senate, that recognised it as a legal entity. These initiatives go beyond the instrumental use of law, which reduces personality to a “legal fiction” that can be attributed to non-individual entities such as associations, companies, and states. Instead, they accompany or translate deeper social and cultural transformations, expressing how the inhabitants of a territory cultivate their relationships with all living beings.18 Such rights pave the way for new potential forms of inventive autochthonies within Western contexts, outlining the contours of a democracy of the living at the scale of territories of life. There is then an urgent need to invent river-institutions and accompanying river-stories.19

3.3 Water peoples and their hydroworlds

In the paradigmatic case of the personification of the Whanganui River by the Māori in New Zealand, the river ecosystem in its entirety and its uniqueness, including the human collectives that inhabit its banks, is recognised as a legal entity under the name of “Te Awa Tupua.” As the Māori adage states – “I am the river and the river is me” –, the territory of the river is not regarded as a set of natural resources or as a surface to be managed, but as a collective, relational, and open entity. For the Māori, the social bond between humans also constitutes a body together with the territory, with life forms that traverse it and are interwoven within it. The objective of “good politics” is no longer to act only in the interest of human societies, independently of their relations with non-humans, but rather to act from within the environment itself, considering the health and well-being of the different relational scales that constitute the collective subject of the river. Human beings become members of a body-territory that they contribute to regenerate and reactivate, reinventing vernacular gestures, knowledges, and know-how to renew alliances with non-humans and give birth to water peoples and their hydroworlds.

3.4 A pluriversal Earth

If the modern state institutions established in Europe emerged in response to the delegitimization of divine-right political regimes – replacing divine authority with the authority of a self-governing Humanity – then the rights of the Earth reflect a new source of authority and normativity: that of the Earth itself. Non-humans, animals, forests, soils, waters, winds, now enter the social and political space to question its foundations, making visible the bonds of interdependence that bind us to them. Alongside these non-human entities, the cultures and ways of life suppressed by colonial modernity are resurfacing, pointing toward the vision of pluriversal democracies,20 capable of connecting manifold worlds grounded in living territories. The Earth is not merely the globe – an abstract, homogenized entity manageable by distant expertise – but rather an inhabited Earth, comprising a plurality of worlds: an Earth of many worlds, a pluriverse. The objective of a terrestrial diplomacy, then, is to support the emergence of diverse ways of worldmaking and foster their dialogue and interaction. In other words, we need to build an inter-world of water-peoples.

Indigenous struggles and declarations of the rights of Mother Earth in Ecuador (2008) and Bolivia (2010) have sparked significant institutional innovations across continents: in Colombia, India, New Caledonia, New Zealand, Canada. In Europe, between 2019-2021, several initiatives emerged: in the Loire, the Rhône, and the Tavignanu, local communities have mobilized to demand legal recognition of the rights of their rivers and the ecosystems they inhabit.

In October 2023, the Mar Menor lagoon in Murcia, Spain, became the subject of a popular law, validated by the Spanish Senate, that recognised it as a legal entity. These initiatives go beyond the instrumental use of law, which reduces personality to a “legal fiction” that can be attributed to non-individual entities such as associations, companies, and states. Instead, they accompany or translate deeper social and cultural transformations, expressing how the inhabitants of a territory cultivate their relationships with all living beings.18 Such rights pave the way for new potential forms of inventive autochthonies within Western contexts, outlining the contours of a democracy of the living at the scale of territories of life. There is then an urgent need to invent river-institutions and accompanying river-stories.19

3.3 Water peoples and their hydroworlds

In the paradigmatic case of the personification of the Whanganui River by the Māori in New Zealand, the river ecosystem in its entirety and its uniqueness, including the human collectives that inhabit its banks, is recognised as a legal entity under the name of “Te Awa Tupua.” As the Māori adage states – “I am the river and the river is me” –, the territory of the river is not regarded as a set of natural resources or as a surface to be managed, but as a collective, relational, and open entity. For the Māori, the social bond between humans also constitutes a body together with the territory, with life forms that traverse it and are interwoven within it. The objective of “good politics” is no longer to act only in the interest of human societies, independently of their relations with non-humans, but rather to act from within the environment itself, considering the health and well-being of the different relational scales that constitute the collective subject of the river. Human beings become members of a body-territory that they contribute to regenerate and reactivate, reinventing vernacular gestures, knowledges, and know-how to renew alliances with non-humans and give birth to water peoples and their hydroworlds.

3.4 A pluriversal Earth

If the modern state institutions established in Europe emerged in response to the delegitimization of divine-right political regimes – replacing divine authority with the authority of a self-governing Humanity – then the rights of the Earth reflect a new source of authority and normativity: that of the Earth itself. Non-humans, animals, forests, soils, waters, winds, now enter the social and political space to question its foundations, making visible the bonds of interdependence that bind us to them. Alongside these non-human entities, the cultures and ways of life suppressed by colonial modernity are resurfacing, pointing toward the vision of pluriversal democracies,20 capable of connecting manifold worlds grounded in living territories. The Earth is not merely the globe – an abstract, homogenized entity manageable by distant expertise – but rather an inhabited Earth, comprising a plurality of worlds: an Earth of many worlds, a pluriverse. The objective of a terrestrial diplomacy, then, is to support the emergence of diverse ways of worldmaking and foster their dialogue and interaction. In other words, we need to build an inter-world of water-peoples.

4. Terrestrial diplomacy and politics of hospitality: creating situated alliances and solidarity networks

The horizon of a pluriversal Earth compels us to reinvent the forms of diplomacy. This task extends beyond the modern nation-state paradigm, which was primarily designed to prevent war between nations,21 and assumed war as the foundation of politics.22 Instead, diplomacy must negotiate the interdependencies that sustain the renewal of the different forms of life on Earth.

4.1 Politics of hospitality

The growing climatic instability increasingly threatens the possibility of life (habitability) in many places worldwide, although its precise impacts remain unpredictable: climate refugees, droughts and pollution, soils increasingly unable to feed us, etc. Today we are confronted – even if we are reluctant to admit it – with a whole series of new threats to hospitality.

The modern model of state diplomacy is inadequate to respond to these issues, since it is based on the political paradigm of national sovereignty, which owns a territory against a “foreigner,” always perceived as potentially hostile. Playing on the double meaning of the Greek word “hostis,” which means both enemy and guest (the guest and the host), we could say that the mandate of a terrestrial diplomacy is to transform the enemy into a guest,23 a politics of war into a politics of hospitality.

This poses new challenges that question the fundamental values of our political modernity: How shall we care for a polluted river? How can we respond to the mass extinction of species? How can we listen to a melting glacier and the relationships of interdependence that shape it and are nourished by it? How can we join forces upstream and downstream of the river, to regenerate the cycles of life? How is it possible to respond collectively to floods, inundations, wildfires, storms? At what scales, and in what ways, solidarity between living beings can be renewed, considering the specificities of each territory and the diverse modes of inhabitation? These are the questions that the terrestrial diplomacy that we are envisioning here must attempt to answer.

Such diplomacy can only take shape through the needs of the inhabiting communities. Which are the first that, now and in the future, suffer the consequences of ecological disasters.

4.2. A diplomacy for agonistic conflicts

These disruptions are likely to increase conflicts over terrestrial commons (water, land, air), with the risk that certain groups will attempt to dominate or monopolize these commons at the expense of others. How can we collectively address these conflicts without reproducing the political paradigm of war, which is based on the opposition between friends and enemies24 and implies the victory of one side through the annihilation, or submission, of the other? How can we deal with conflicts from the perspective of care and hospitality?

To achieve this, we propose revising the model of political action: from a top-down approach to an agonistic practice.25 This will change the nature of diplomacy, since the primary objective will no longer be protecting one group’s interests over another’s, but facilitating collective transformation by considering the tensions, conflicts over usage, and clashes of worldviews that emerge in the shared experience of territorial cohabitation. For example: by exposing the incompatibility between certain chains of interdependence (corn, pesticides, intensive production, long-distance transport, oil consumption) and their own conditions of existence (presence of water, biodiversity, fertility of the land); by articulating new chains of interdependence; or by creating new alliances and transversal connections among different groups of inhabitants. Agon fosters “a decentring of individuals in favor of the relationships that condition their existence within a place of life in common, taking into account the way in which the different beings that inhabit or attend the place are affected by the conflict.”26 It opens the space-time of a negotiation of interdependencies.

From the perspective of an agonistic politics, terrestrial diplomacy thinks and establishes the conditions for welcoming the other upon whom we depend, thus allowing the reciprocal transformation that such welcome demands: giving in exchange what has been given to us, recognizing the bond of obligation that the gift institutes.

The diplomat acts on the threshold, on the border, on the dividing line, but his objective is no longer to guarantee the immunity of the collective (national) body against the foreigner. On the contrary, the diplomat’s role is to negotiate forms of passage, transition, and transformation: an agent of connections guaranteeing the counter-gift. Diplomatic action becomes more than the translation between two cultures (political, linguistic, cultural and social); it is a process of transduction at the service of a collective metamorphosis: transduction referring to “the operation by which two or more orders of incommensurable realities enter into resonance and become commensurable by the invention of a dimension that articulates them, and by the passage to an order richer in structures.”27

The diplomat is a world-passer.28 To respond to the diversity of world-making practices and enabling dialogue, diplomacy cannot be conceived as pre-existing the conflict, in the form of a constituted body; it must be invented, in a situation, taking into account the singularity of the conflict that has arisen. Diplomatic action therefore consists in the invention of spaces and functions capable of articulating transduction by negotiating the terrestrial alliances necessary for the renewal of the different forms of life that weave the web of bodies-territories.

It contributes to the coming into being of what the anthropologist Arturo Escobar calls “pluriversal contact zones:” space-times of encounter and transition between worlds and ways of inhabiting territories.

4.3 Caring for bodies-territories

A terrestrial diplomacy acquires its meaning through a threefold gesture:

1. By addressing conflicts at their source, that is, in the territories of life, with the actors and actresses concerned, in order to collectively heal the wounds inflicted by ecological catastrophes and question the logic of hoarding and domination.

2. By caring for vital interdependencies, by inventing situated eco-socialities and solidarities between humans and non-humans.

3. By creating the conditions for an intercultural and interspecific dialogue, and nurturing the cohabitation between a plurality of ways of making the world.

A terrestrial diplomacy must design other distributions and passages within the territories inhabited in common. It constitutes an essential element for recomposing political territorialities, from and with the cycles of life, on the horizon of a pluriversal Earth.

5. A Diplomatic Council in the Lake Geneva area: an institutional process for United River Basins

Geneva is strategically located in the heart of the Rhône River basin. But it is also a city that has maintained, since the Middle Ages, an ambiguous relationship with its territory. The Reformation made Geneva an independent city, an island in the middle of a hostile territory; and then the accession to the Swiss Confederation after the Napoleonic Wars granted it a status of neutrality and impartiality. From then on, as Geneva was not anchored to its own territory, it could be the place where States discussed their divergences, where the various constituted and recognized political bodies of the planet could peacefully meet.

5.1 Leman: a place of interglobal diplomacy

However, Geneva is a real city, surrounded by a real countryside, on the shores of a real lake, Lake Geneva, through which flows the Rhône River and several of its tributaries, in particular the Arve, but also smaller rivers such as the Allondon or the Laire. Uniquely, the Geneva metropolitan area straddles two countries: its Swiss part is nearly encircled by French territory, with only 6 kilometres of a shared border connecting it with the rest of Switzerland. The demands of cross-border governance are complex and difficult to address, because political territories do not have the same competences at the local level, even if the problems related to rivers are increasingly becoming crucial, as can be seen with regard to the flow of the Rhône – which depends in the long term on the preservation of glaciers at its source, and it is critical to the French economy since several nuclear power plants are located along its course.

A terrestrial diplomacy acquires its meaning through a threefold gesture:

1. By addressing conflicts at their source, that is, in the territories of life, with the actors and actresses concerned, in order to collectively heal the wounds inflicted by ecological catastrophes and question the logic of hoarding and domination.

2. By caring for vital interdependencies, by inventing situated eco-socialities and solidarities between humans and non-humans.

3. By creating the conditions for an intercultural and interspecific dialogue, and nurturing the cohabitation between a plurality of ways of making the world.

A terrestrial diplomacy must design other distributions and passages within the territories inhabited in common. It constitutes an essential element for recomposing political territorialities, from and with the cycles of life, on the horizon of a pluriversal Earth.

5. A Diplomatic Council in the Lake Geneva area: an institutional process for United River Basins

Geneva is strategically located in the heart of the Rhône River basin. But it is also a city that has maintained, since the Middle Ages, an ambiguous relationship with its territory. The Reformation made Geneva an independent city, an island in the middle of a hostile territory; and then the accession to the Swiss Confederation after the Napoleonic Wars granted it a status of neutrality and impartiality. From then on, as Geneva was not anchored to its own territory, it could be the place where States discussed their divergences, where the various constituted and recognized political bodies of the planet could peacefully meet.

5.1 Leman: a place of interglobal diplomacy

However, Geneva is a real city, surrounded by a real countryside, on the shores of a real lake, Lake Geneva, through which flows the Rhône River and several of its tributaries, in particular the Arve, but also smaller rivers such as the Allondon or the Laire. Uniquely, the Geneva metropolitan area straddles two countries: its Swiss part is nearly encircled by French territory, with only 6 kilometres of a shared border connecting it with the rest of Switzerland. The demands of cross-border governance are complex and difficult to address, because political territories do not have the same competences at the local level, even if the problems related to rivers are increasingly becoming crucial, as can be seen with regard to the flow of the Rhône – which depends in the long term on the preservation of glaciers at its source, and it is critical to the French economy since several nuclear power plants are located along its course.

5.2 For a Europe of United River Basins

Geneva is shaped by a long experience of human diplomacy and a contradictory and complex relationship with its own territory. Since the end of the last century, the city has begun to take care of its waterways through major renaturalization projects, especially on the Aire and the Seymaz (tributaries of the Arve), carried out between 2000 and 2010. Geneva is also a Swiss city, a country that welcomes in its Alpine territory the sources of two of the main rivers of Western Europe, the Rhine and the Rhône, but also the Inn and the Ticino (two major tributaries of the Danube and the Po). Because of its numerous glaciers, Switzerland is considered the “water tower of Europe.” These rivers cross borders, unlike the Loire, which belongs to only one nation. So, from a Swiss perspective, a reflection on the watersheds is from the outset a cross-border problem. Geneva is also a place of non-state and informal diplomacy, where many NGOs and citizen groups mobilize on all kinds of issues. This city is a place of encounters.

For all these reasons, it seems appropriate to establish in Geneva the Diplomatic Council of River Basins, in a city characterized by a unique geographical and historical experience.

5.3 An Earth Council for a pluriversal culture

The Diplomatic Council of River Basins will serve as a space for dialogue between the different constituent dynamics in the territories, at both a European and global level. A space for dialogue where human and non-human actors and actresses will have the chance to exchange, advocating for their places of life, and for the challenges and struggles necessary to sustain and enhance the environments that unfold there. Based in Geneva, the Diplomatic Council of River Basins will be a space open to world conflicts, present in various European and international river basins.

The Diplomatic Council of River Basins will also provide resources for thoughts and struggles, with the goal of achieving a progressive autonomy of the river basins and their confederation. Insights from unique experiences across different continents will be shared to promote a real inter-world coordination of indigenous ways of life. The Council will also be a place for debating the political and legal strategies best suited to making the voice of non-human actors and actresses recognized.

Geneva is shaped by a long experience of human diplomacy and a contradictory and complex relationship with its own territory. Since the end of the last century, the city has begun to take care of its waterways through major renaturalization projects, especially on the Aire and the Seymaz (tributaries of the Arve), carried out between 2000 and 2010. Geneva is also a Swiss city, a country that welcomes in its Alpine territory the sources of two of the main rivers of Western Europe, the Rhine and the Rhône, but also the Inn and the Ticino (two major tributaries of the Danube and the Po). Because of its numerous glaciers, Switzerland is considered the “water tower of Europe.” These rivers cross borders, unlike the Loire, which belongs to only one nation. So, from a Swiss perspective, a reflection on the watersheds is from the outset a cross-border problem. Geneva is also a place of non-state and informal diplomacy, where many NGOs and citizen groups mobilize on all kinds of issues. This city is a place of encounters.

For all these reasons, it seems appropriate to establish in Geneva the Diplomatic Council of River Basins, in a city characterized by a unique geographical and historical experience.

5.3 An Earth Council for a pluriversal culture

The Diplomatic Council of River Basins will serve as a space for dialogue between the different constituent dynamics in the territories, at both a European and global level. A space for dialogue where human and non-human actors and actresses will have the chance to exchange, advocating for their places of life, and for the challenges and struggles necessary to sustain and enhance the environments that unfold there. Based in Geneva, the Diplomatic Council of River Basins will be a space open to world conflicts, present in various European and international river basins.

The Diplomatic Council of River Basins will also provide resources for thoughts and struggles, with the goal of achieving a progressive autonomy of the river basins and their confederation. Insights from unique experiences across different continents will be shared to promote a real inter-world coordination of indigenous ways of life. The Council will also be a place for debating the political and legal strategies best suited to making the voice of non-human actors and actresses recognized.

Objectives of the Diplomatic Council

To be a place of interspecific diplomacy to address debates, controversies, and conflicts of use at the scale of watersheds, grounded on the dynamics of inhabitants;

To become a source-place that makes re-inhabitation practices visible and defends the rights and commons of use;

To think and gather tools to defend the communities of inhabitants (legal tools, exchange of knowledges and know-how, collective links/associations/ researchers...);

To be a space for dialogue between different institutional strategies (popular assemblies, territorial unions, defence of common goods, rights of nature...);

To produce an ecocentric culture (learning territories, community knowledge, environmental humanities).

April 2024, Geneva.

To be a place of interspecific diplomacy to address debates, controversies, and conflicts of use at the scale of watersheds, grounded on the dynamics of inhabitants;

To become a source-place that makes re-inhabitation practices visible and defends the rights and commons of use;

To think and gather tools to defend the communities of inhabitants (legal tools, exchange of knowledges and know-how, collective links/associations/ researchers...);

To be a space for dialogue between different institutional strategies (popular assemblies, territorial unions, defence of common goods, rights of nature...);

To produce an ecocentric culture (learning territories, community knowledge, environmental humanities).

April 2024, Geneva.

This text was written within the framework of the event “Ces jours terrestres”, organized by Utopiana in Geneva, which hosts the project of the Diplomatic Council of River Basins. It has been first published on the platform «Terrestres» in 2024. Learn more about Terrestres here.

About the authors: learn more about the authors here

About the authors: learn more about the authors here

Footnotes

1

See Les Veines de la Terre: une anthologie des bassins-versants, F. Guerroué, M. Rollot & M. Schaffner, Wildproject, 202.

2

See Qu’est-ce qu’une biorégion?, Mathias Rollot & Marin Schaffner, Wildproject, 2021.

3

Ibid.

4

We borrow this expression from Mayan ecofeminist activists in Guatemala. See «’Corps-territoire et territoire-Terre’ : le féminisme communautaire au Guatemala. Entretien avec Lorena Cabnal », Cahiers du Genre, vol. 59, no. 2, 2015, pp. 73-89. See also Vivantes, des femmes qui luttent en Amérique latine, éd. Dehors, 2023.

5

By “body-territory” we mean the web of interdependencies between bodies (human and non-human), from which earthly communities and bioregions are formed. See Sophie Gosselin & David gé Bartoli, La condition terrestre, habiter la Terre en communs, éd. du Seuil, 2022, chap. 4.

6

See Sophie Gosselin et David gé Bartoli, La condition terrestre, habiter la Terre en communs, Seuil, 2022, chap.4.

7

Sophie Gosselin «Pour une Europe des Versants-Unis», in Reconstruire la pensée européenne, dir. Dominique Bourg, éd. Hermann, 2024.

8

See Sophie Gosselin et David gé Bartoli, La condition terrestre, habiter la Terre en communs, Seuil, 2022, chap. 4.

9

See «Pour une intermondiale des bassins-versants», in Les Veines de la Terre: une anthologie des bassins-versants, F. Guerroué, M. Rollot & M. Schaffner, Wildproject, 2021.

10

To use the title of the symposium organized by Mathias Rollot & Marin Schaffner in May 2024: https://cerisy-colloques.fr/eau2024/

11

Vandana Shiva, Mémoires terrestres, trad. Marin Schaffner, Rue de l’Echiquier/Wildproject, 2023.

12

See Hydromondes, «La biorégion, creuset d’une démocratie directe de l’eau», Bascules, 2023.

13

Hatakeyama Shigeatsu, La Forêt amante de la mer, Wildproject, 2019.

14

Since December 2021, the European Parliament has legally recognized the crime of ecocide. On the question of ecocide, see Valérie Cabanes, Un nouveau droit pour la Terre, Seuil, 2016.

15

Universal Declaration of the Rights of Mother Earth, adopted in 2010 at the World Conference of Peoples against Climate Change, on the initiative of the Amerindian peoples, who are calling for the UN to adopt the Declaration. https://www.rightsofnaturetribunal.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/ENG-Universal-Declaration-of-the-Rights-of-Mother-Earth.pdf

16

See Qu’est-ce qu’une biorégion?, Mathias Rollot & Marin Schaffner, Wildproject, 2021.

17

Pablo Solón, «Le ‘buen vivir’, une autre vision du monde», Revue Projet, vol. 362, no. 1, 2018, pp. 66-72.

18

See Sophie Gosselin et David gé Bartoli, La condition terrestre, ibid.

19

See «Pour une intermondiale des bassins-versants», in Les Veines de la Terre: une anthologie des bassins-versants, F. Guerroué, M. Rollot & M. Schaffner, Wildproject, 2021.

20

Plurivers: un dictionnaire du post-développement, Wildproject, 2023.

21

Laurence Badel et Stanislas Jeannesson, «Une histoire globale de la diplomatie?», Diplomaties, éd. Armand Colin, 2014.

22

As Clausewitz's famous phrase suggests, “war is the continuation of politics by other means”. The very meaning of political activity only seems to make sense against the backdrop of a permanent state of war, articulated around the opposition of friend and foe.

23

Even if it does confuse us. Acceptance of transformation is a condition of hospitality, but also, more generally, of life.

24

See Carl Schmitt, Le nomos de la Terre, PUF, 2001.

25

“Agone” was the ancient Greek term for the art of regulated combat. For an in-depth look at its political meaning, see Sophie Gosselin et David gé Bartoli, La condition terrestre, habiter la Terre en communs, éd. Seuil, 2022, chap. 3.

26

See Qu’est-ce qu’une biorégion?, Mathias Rollot & Marin Schaffner, Wildproject, 2021.

27

See Qu’est-ce qu’une biorégion?, Mathias Rollot & Marin Schaffner, Wildproject, 2021.

28

See David gé Bartoli et Sophie Gosselin, Le toucher du monde – techniques du naturer, éd. Dehors, 2019.

1

See Les Veines de la Terre: une anthologie des bassins-versants, F. Guerroué, M. Rollot & M. Schaffner, Wildproject, 202.

2

See Qu’est-ce qu’une biorégion?, Mathias Rollot & Marin Schaffner, Wildproject, 2021.

3

Ibid.

4

We borrow this expression from Mayan ecofeminist activists in Guatemala. See «’Corps-territoire et territoire-Terre’ : le féminisme communautaire au Guatemala. Entretien avec Lorena Cabnal », Cahiers du Genre, vol. 59, no. 2, 2015, pp. 73-89. See also Vivantes, des femmes qui luttent en Amérique latine, éd. Dehors, 2023.

5

By “body-territory” we mean the web of interdependencies between bodies (human and non-human), from which earthly communities and bioregions are formed. See Sophie Gosselin & David gé Bartoli, La condition terrestre, habiter la Terre en communs, éd. du Seuil, 2022, chap. 4.

6

See Sophie Gosselin et David gé Bartoli, La condition terrestre, habiter la Terre en communs, Seuil, 2022, chap.4.

7

Sophie Gosselin «Pour une Europe des Versants-Unis», in Reconstruire la pensée européenne, dir. Dominique Bourg, éd. Hermann, 2024.

8

See Sophie Gosselin et David gé Bartoli, La condition terrestre, habiter la Terre en communs, Seuil, 2022, chap. 4.

9

See «Pour une intermondiale des bassins-versants», in Les Veines de la Terre: une anthologie des bassins-versants, F. Guerroué, M. Rollot & M. Schaffner, Wildproject, 2021.

10

To use the title of the symposium organized by Mathias Rollot & Marin Schaffner in May 2024: https://cerisy-colloques.fr/eau2024/

11

Vandana Shiva, Mémoires terrestres, trad. Marin Schaffner, Rue de l’Echiquier/Wildproject, 2023.

12

See Hydromondes, «La biorégion, creuset d’une démocratie directe de l’eau», Bascules, 2023.

13

Hatakeyama Shigeatsu, La Forêt amante de la mer, Wildproject, 2019.

14

Since December 2021, the European Parliament has legally recognized the crime of ecocide. On the question of ecocide, see Valérie Cabanes, Un nouveau droit pour la Terre, Seuil, 2016.

15

Universal Declaration of the Rights of Mother Earth, adopted in 2010 at the World Conference of Peoples against Climate Change, on the initiative of the Amerindian peoples, who are calling for the UN to adopt the Declaration. https://www.rightsofnaturetribunal.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/ENG-Universal-Declaration-of-the-Rights-of-Mother-Earth.pdf

16

See Qu’est-ce qu’une biorégion?, Mathias Rollot & Marin Schaffner, Wildproject, 2021.

17

Pablo Solón, «Le ‘buen vivir’, une autre vision du monde», Revue Projet, vol. 362, no. 1, 2018, pp. 66-72.

18

See Sophie Gosselin et David gé Bartoli, La condition terrestre, ibid.

19

See «Pour une intermondiale des bassins-versants», in Les Veines de la Terre: une anthologie des bassins-versants, F. Guerroué, M. Rollot & M. Schaffner, Wildproject, 2021.

20

Plurivers: un dictionnaire du post-développement, Wildproject, 2023.

21

Laurence Badel et Stanislas Jeannesson, «Une histoire globale de la diplomatie?», Diplomaties, éd. Armand Colin, 2014.

22

As Clausewitz's famous phrase suggests, “war is the continuation of politics by other means”. The very meaning of political activity only seems to make sense against the backdrop of a permanent state of war, articulated around the opposition of friend and foe.

23

Even if it does confuse us. Acceptance of transformation is a condition of hospitality, but also, more generally, of life.

24

See Carl Schmitt, Le nomos de la Terre, PUF, 2001.

25

“Agone” was the ancient Greek term for the art of regulated combat. For an in-depth look at its political meaning, see Sophie Gosselin et David gé Bartoli, La condition terrestre, habiter la Terre en communs, éd. Seuil, 2022, chap. 3.

26

See Qu’est-ce qu’une biorégion?, Mathias Rollot & Marin Schaffner, Wildproject, 2021.

27

See Qu’est-ce qu’une biorégion?, Mathias Rollot & Marin Schaffner, Wildproject, 2021.

28

See David gé Bartoli et Sophie Gosselin, Le toucher du monde – techniques du naturer, éd. Dehors, 2019.