Text, photographs, and illustrations

by Lucia Ruocco and Sara Corrado

Header image by Pelatina1

︎

January 27, 2025

“San Martino Valle Caudina is located in the Valle Caudina, a plain between the Caserta, Benevento, Avellino, and Nola areas”. These were the first words we heard as students of the master’s program in Environmental Humanities at Roma Tre University2. Our journey of discovery and research in this territory took place in July 2024, as part of the four-day Summer School Motus Terrae. Scuola metarurale3.

Our aim as students was to interpret post-catastrophe scenarios through knowledge-exchange and action-research. This experience provided us with the opportunity to experiment with new research tools and practices, fostering both personal and professional growth.

The first question we asked ourselves, at the outset of our inquiry, was about the ‘how’. We knew that our actions could not ‘give voice’ to this territory, as San Martino was already speaking to us in many voices: those of humans, plants, animals, and sounds that still don’t have categories that satisfy us: like the buzzing of wasps and butterflies in the air, the grunting of wild boars sneaking into the courtyards of abandoned houses, the sound of the wind slamming against the concrete dams beyond the old mill and just before the Partenio's mountains, the slow sliding of the ground on the lava stone floor when someone or something steps on it, the reggaeton blaring from the little bar in the square at the time of an aperitif, or the thousand voices singing karaoke in the ancient center every evening from 9 PM onwards, and the constant flow of the Caudino stream that informs the town of unknown soils and towering peaks. It is precisely this final element, and the multiple and diverse imaginaries linked to it, that inspired us to weave our story.

San Martino Valle Caudina

San Martino Valle Caudina is a village of architectural contrasts, with some streets paved in marble and others constructed from lava stone. The village rests on the slopes of Mount Pizzone, part of the Southern-Apennine range of Partenio, about 50 km inland from Naples. Despite its solemn appearance, this mountain is far from static. Over time, approximately four meters of pyroclastic material have accumulated on its predominantly carbonate and limestone rocks. Volcanic ash from various eruptions of the Vesuvius has settled here, often blending with the local rock layers. The fusion of diverse soils and materials has fostered the growth of the chestnut tree, which has long been a vital source of income for many residents of San Martino.

As one villager told us, "As long as we took care of the mountain, especially with the many industries that relied on the chestnut tree, it didn’t cause us much trouble". However, they added, "Since the chestnut trees have become diseased, the people of San Martino have abandoned the mountain”. In the popular imagination, this neglect is tied to the various landslides the village has endured over the years.

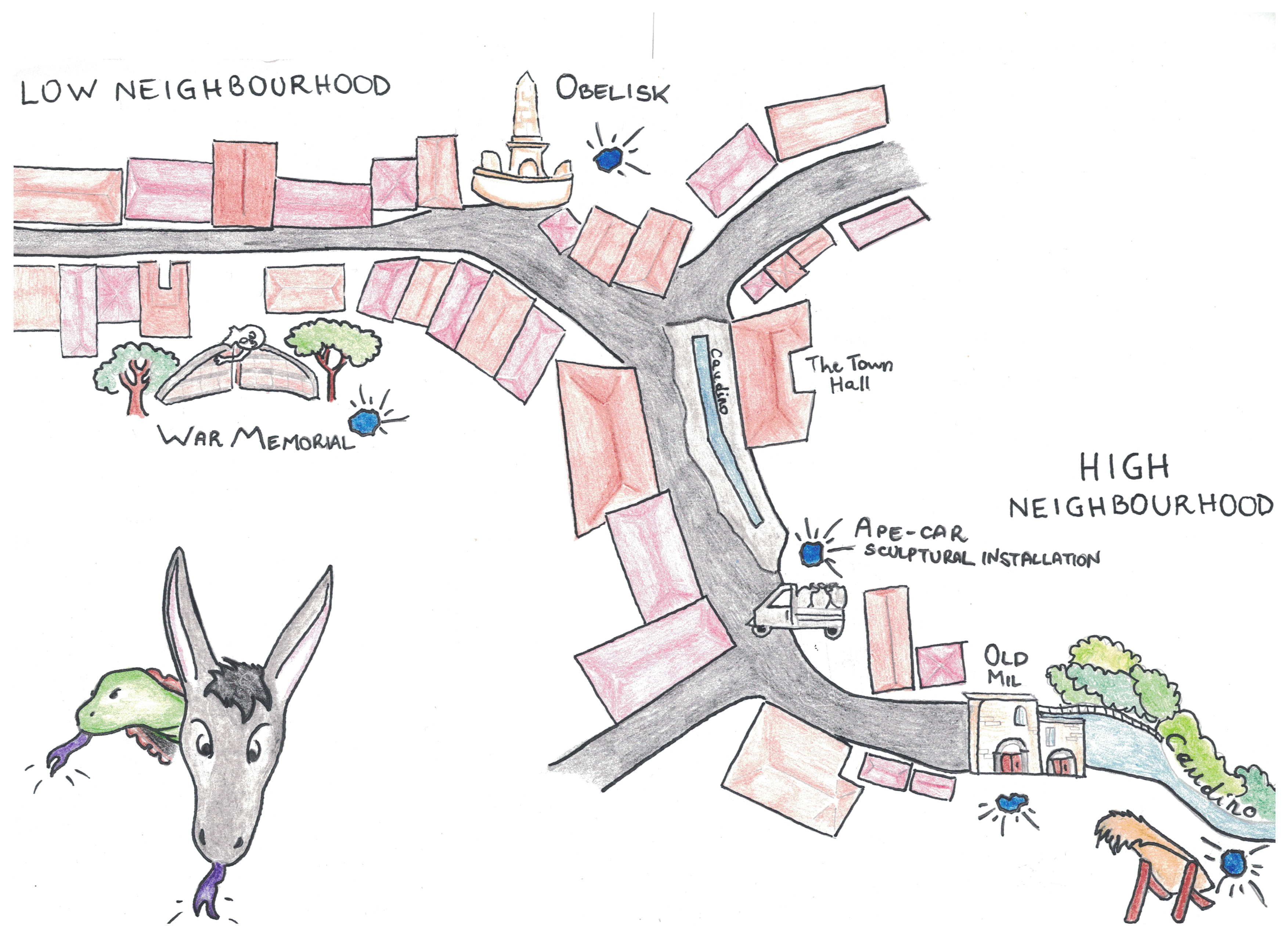

The most recent event occurred on December 22, 20194, when several days of heavy rainfall caused the ground, along with everything rooted and anchored to it, to slide down into the valley, blocking the culvert in the village centre through which the Caudino stream flowed. That night, the torrent, which had been buried beneath the ground for years, surged, all the way to the Town Hall. It took several days of investigation to trace the stream's actual underground path. Today, the torrent flows openly alongside the foundations of the municipal building. After a lengthy and challenging decision-making process, the residents of San Martino chose not to cover it again. Recently, discussions have arisen about unblocking the upper section of the river, stretching from the Mulino Vecchio to the center of the roundabout (as shown in the picture). But that’s another story.

What Emerged

What we knew for certain about the task assigned to us during this week of Summer School was that our role was not to resolve the debate surrounding the management of the stream or to conduct a detailed, comprehensive analysis of San Martino. Instead, we were invited to immerse ourselves in the territory: walking through it, observing it, listening to it, and engaging with its inhabitants. In essence, we embraced the unexpected with an open mind.

We embraced a form of derivation that enabled us to build a bridge with our surroundings, free from the constraints of worrying about the restitution we might eventually provide. Instead, we immersed ourselves in the process that began unfolding within us from the very first day of exploration. The diverse encounters we experienced with the territory inspired reflections in us that were both complementary and harmonious. At this stage, our research focused on the symbolic imagery that the human community of San Martino—particularly its children—had developed around the Caudino torrent. Rather than defining it as purely monstrous or magical, as either a force of salvation or destruction, we sought to understand the evolving interpretations of the landscape shaped by and surrounding this watercourse. This includes perceptions formed in the wake of the 2019 landslide and those rooted in a much older history.

A map of the area, with the Old Mill as a boundary

between the two neighborhoods.

Often regarded as polluted, corrupt, dangerous, inconvenient, and somewhat detached, it is no coincidence that the Caudino route is bisected by the Old Mill, symbolizing a structural fragmentation of the village itself. The Old Mill acts as a boundary between the upper neighborhood, characterized by its rugged, uneven terrain where the torrent has always flowed openly under the sky, and the lower neighborhood, which is flatter and more orderly. In the lower area, settlement density increases, but there is significantly less interaction with the Caudino—prior to the 2019 flood, this section of the torrent was entirely covered.

The upper neighbourhood remains a place that, despite efforts at restoration to improve its viability, still attracts very few visitors. Many homes that were once inhabited are either abandoned or for sale.

The Mill, once a bustling hub that harnessed the canal’s waterpower to connect two areas, now stands dormant—its windows and doors shuttered. From below, it is impossible to glimpse what lies beyond its walls. Just a few steps behind it, a stream teems with life, home to countless insects, diverse grasses, and wild boars that venture down to drink from the valley.

This stands in stark contrast to the torrent near the town hall, confined to a narrow channel flanked by iron railings and steep embankments—a heavily tamed waterway. On one side, there is the illusion of human mastery over nature; on the other, the untamed mountain thrives, letting its flanks flow freely.

The urban structure of San Martino reflects an attitude characteristic of post-traumatic experiences: the repressed. The clear separation between village life and mountain life—symbolized by the large mill with its sealed gates—suggests an attempt to distance the source of a deep wound from the collective imagination. This is a trauma that remains unprocessed, resurfacing not only in the spatial organization. In the upper part of the village, nearly all the houses are uninhabited. Many residents have moved to the flatter area in the valley, known as 'the country,' where the effects of landslides were less severe.

In the upper part of the village, although the stream has more space and less concrete around it, the landscape remains beautiful to admire. However, neither municipal efforts nor a small craft ladder provide easy access to the river for the people of San Martino. Few inhabitants have meaningful contact with the torrent; only the most daring venture to swim at a specific point where the water gathers in a small basin. The noise of the water, particularly near the drops, can be bothersome for those living in the area.

The intergenerational nature of the trauma is evident in adults forbidding children from getting too close to or touching the water. In this context, a child from San Martino described the stream as ‘dangerous,’ referencing his parents' warnings and a personal, unsettling memory. According to him, a friend once injured his foot while walking in the stream, and the wound never fully healed; he still has a ‘hole’ there to this day. In short, the torrent is viewed as an unpredictable place to avoid, with its bed concealing hidden dangers.

The children looking for the stone, treasure hunting in San Martino Valle Caudina (July 2024).

In Search of a Connection with the Stream: The Treasure Hunt

In his essay Nonhuman Subjects: An Ecology of Earth-Beings (2023), Federico Luisetti explores the relationship between humans and natural ecosystems, which has traditionally been viewed through an anthropocentric lens that sees non-human entities not as active agents, but as resources for human use. The anthropization of nature has led humans to interpret and decode the mountain, the volcano, and the river through a language exclusive to their species, often resulting in domination. This framework leads us to believe we can predict the behaviors of these geo-bodies and form expectations about them. However, the stream is a very different body from ours: it has a will and needs unknown to us. It is we who direct our thoughts toward the stream, not the other way around; its existence is not valid solely in relation to human life or as a resource to be exploited. It exists and acts independently of human intentions. "Rocks are subjects without being persons," but "if a stone is not a person, what is it for humans?"(16). What, then, does the stream represent for San Martino Valle Caudina? Is it possible to create a new form of dialogue and connection with this geo-body?

Starting with these questions, we set out to explore how we could spark our reflections. You could say we threw a stone into the water, hoping to see the ripples spread.

We decided to engage the town's children, partly because many of them had only experienced the trauma of the stream’s flooding peripherally, and partly because, with their fresh perspectives, it seemed easier to imagine building a new form of relationship with the stream. With these considerations in mind, we envisioned a treasure hunt for the children who were in town at the time —a simple and playful way to connect with them and gently guide them to the stream, to see what would unfold.

We had just one day to spread the word about the treasure hunt, so to reach as many children as possible, we contacted the Municipality, the parish, and introduced ourselves at the Pro Loco’s summer camp, while also covering the town center with posters. During our walks, we collected stones from the stream's banks and painted them blue to create a step-by-step trail. Each stone was placed at a key point in the town, accompanied by a note with a clue leading to the next location. The children’s task, of course, was to find all the blue stones, which would guide them to the final destination. There, at the "treasure" site, they would encounter a dissonant scene: a bag of candy and the chance to share their thoughts on the stream.

We selected five locations for the treasure hunt: the first stop was the square with the War Memorial; the second, the (now dry) fountain with the obelisk near the Town Hall; the third, a sculptural installation depicting a three-wheeled ‘ape-car’ carrying water jars (the ‘mummare’); the fourth, the closed gate of the Old Mill; and the last, the stream itself, near a small hut made of wood and straw used by the community for the Nativity scene (upper district). At this final stop, the blue stone was placed in the streambed, intentionally creating a dissonant situation to spark the children’s curiosity and open up a conversation about the watercourse. Some children stood frozen in place, others felt tricked, while some tried to figure out how to climb over the fence and jump in to grab the elusive last stone —something they couldn’t do, at least in our presence, due to the lack of structures to facilitate descent.

It was precisely around this absurd and emotional situation that we seized the opportunity to ask the children about their thoughts and feelings regarding the stream. Some openly expressed their fear of approaching it, seeing it as dangerous. One of them, Marco, began by saying, “If I fall into the river, I don’t know where I’ll end up!” He then strengthened his point about the stream’s danger with a statement of great symbolic value: “There are poisonous turtles and donkeys in the stream!”

Derive

Marco's statement, and the symbols within it, bring us back to the core of our journey. It represents one of the possible mappings of this collective imaginative process: from which, in which, and with which to “derive”5. To explore this process, we will draw on Jung’s theory of the collective unconscious, as well as the work of Eduardo Kohn. In his book How Forests Think, Kohn explores how to approach the symbolic meanings generated from/in/with the forest, in a way that transcends the anthropocentric perspective:

"Forests think, and these thoughts are made manifest in the forms of images, signs, and relations that can cross species boundaries. [...] To understand this nonhuman thinking, we must ourselves engage in a form of thought that is more open to the kinds of semiotic exchanges that characterize the living world. This is why it is so important to enter the world of dreams, this dreamlike space of image associations" (Kohn 2013, 163).

Similarly, Carl Gustav Jung, in The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious, argues that within a deeper layer of the psyche, which he identifies as the "collective unconscious," reside universal structures shared by all of humanity, expressing themselves through symbols and images (Jung 1959). These structures, or forms, known as "archetypes," are believed to be inherited. Jung posits that individuals do not enter the world as blank slates, but rather come with a rich reservoir of experiences stored in the deepest recesses of their psyche:

"Man is 'possessed' of many things he has never acquired, but has inherited from his ancestors. [...] Just as in the bird the migratory instinct and the instinct to build a nest are never learned or individually acquired, so too man at his birth contains the fundamental fabric of his being, not only of his individual nature but also of the collective" (Jung 1998, 67).

Integrating the theories of Carl Gustav Jung and Eduardo Kohn reveals that the human mind does not think ‘outside the world’ but is constituted within it. In this sense, it speaks and exists through a legacy of symbols and relationships passed down over time. This inheritance can be understood as the sedimentation of semiotic exchanges that emerge within the ecosystems to which humans belong. Here, we aim to expand the Jungian concept of the collective unconscious to include non-humans—not as passive recipients, but as active participants in the creation of this legacy. In analyzing this pluriverse of signs, symbols, and representations, we seek to "understand how form emerges and propagates in the forest and in the lives of those who engage with it – be they river dolphins, hunters, or rubber barons" (Kohn 2013, 10) – or poisonous turtles and donkeys.

Returning to Marco's statement, we ask: what do the images shaped by his imagination seek to express? Which archetypes and semiotic exchanges drive this dialogue with the Caudino torrent ecosystem? On one hand, there is the symbol of the donkey, extensively investigated by Giovanni Greco’s article (2006). This animal has been “for centuries the personification of ignorance and diabolical obstinacy, [...] at the same time the animal that knows most because it knows it does not know”. Its ignorance, patience and stubbornness constitute the allegory of the truth-seeker. Indeed, “the braying is, among the voices of nature, one of the most dramatic, an expression of an irremediable urgency and the will to remain silent no longer, after having been for too long”. In this context, we can associate the donkey with the Jungian archetype of the explorer, which symbolises freedom and independence, as well as the pursuit of new experiences and discoveries (Jung 1959). The tortoise, on its part, embodies ancestral meanings of solidity, tradition and wise preservation: “it resembles a little of the ancient silence of life, which in case of danger always knows how to take refuge in itself” (Cesarini Agiroffo 2020). In classical alchemy, the tortoise symbolises the primary substance to which spiritual elements are connected for their embodiment while in Chinese cosmogony, it is regarded as the progenitor of all creatures (Jung 1997). In this context, the tortoise could connect to both the Jungian archetype of the creator – the expression of innovation – and that of the sage – representing wisdom (Jung 1959).

The creatures of Marco’s imagination are poisonous, and Jungian theories of the collective unconscious shed light on them through the archetype of the wounded healer (Jung 1959). This archetype is epitomized by the mythological figure of Chiron, a centaur who is accidentally wounded by his student, Heracles, with a poisoned arrow. The arrow symbolizes a confluence of knowledge (represented by the donkey) and wisdom (represented by the tortoise), as well as suffering and vulnerability (symbolized by the poison). Chiron’s wound causes him enduring pain, which he attempts to soothe using various medicinal herbs. At the same time, the wounded healer is an archetype endowed with a strong regenerative capacity. The figure possesses a deeper comprehension and capability to assist others who are suffering, largely due to his own experience of pain. For Marco, perhaps approaching the stream has always entailed a certain risk: that of being poisoned and becoming the wounded healer. In this interpretation, Marco would be wounded by his own desire for freedom and autonomy (represented by the donkey) and innovation and knowledge (represented by the tortoise).

What if, as Eduardo Kohn suggests (2013), this archetype is not confined to the individual—or, more precisely, does not find its full expression within the individual alone? By stepping away from a strictly psychoanalytic approach and interpreting these symbols through the language of the forest, could we consider that these archetypes pertain to the torrent itself? In this view, the two animals inhabiting the stream embody the torrent as a wounded healer, revealing its healing potential through the material-symbolic legacy that defines it as an ecosystem.

If we accept that the forest "thinks" through the semiotic exchanges—signs, representations, symbols, and relationships—that constitute it, then the Caudino torrent must also think.

In other words, it communicates with the human mind via archetypes within a collective unconscious that extends beyond the human. It might speak of wisdom, symbolized by the tortoise’s ancient stillness of life, and persistence, linked to the donkey’s relentless pursuit of knowledge and growth.

The children sitting next to the river in the upper distric during the round table (July 2024

).

Is an Alliance Possible?

Returning to the treasure hunt, after the symbols emerged and the act of communication unfolded its calming effect, our dialogue with the children shifted back to the material world. How could we create a safe and functional tool to help them descend to and climb back up from the stream? A wooden ladder, perhaps? Or something sturdier, like one made of iron? The children were eager to find a way to reconnect with the stream. Following a roundtable discussion (and after the last of the candy was gone), we decided to head back down to the village together. Before leaving, however, the children asked what to do with the stones they had collected. “You could throw them into the river!” The suggestion sparked excitement, and one by one, they hurried to the railing to make their throws. “You could come back in a few days to see how far they’ve moved,” we added, and this idea was met with joy. We like to think – and it is our responsibility to reflect on – the symbolic meaning of this action, as if saying: “Now, it’s your turn, stream ecosystem!” We hope this act planted the seeds for an ongoing, reciprocal exchange with this geo-body, which, in its own way, joins the game. Perhaps it also sets the stage for other unprecedented encounters between them, with or without us.

In conclusion, the words of the children of San Martino, their imaginative wanderings, provide us with a simple yet effective example of how we can establish a channel of communication with the stream. The turtles, the donkeys, the ladder, and the stones serve as “mediators”, keys to unlocking a new form of contact and dialogue. This does not mean we should now expect to find these fantastical creatures in the Caudino (unfortunately). Rather, Marco's perspective, along with that of the other children, invite us to see something more; they challenge us to imagine a different scenario – not salvific or catastrophic, just different.

Whether we like it or not, the stream exists, and it is up to us to recognize the opportunity to view it not merely as a “sabotaging subject” in human lives, but as a body that lives in and passes through San Martino Valle Caudina, just like its human inhabitants. Since this coexistence takes place anyway, why not open ourselves to the desire to create an alliance?

Returning to the treasure hunt, after the symbols emerged and the act of communication unfolded its calming effect, our dialogue with the children shifted back to the material world. How could we create a safe and functional tool to help them descend to and climb back up from the stream? A wooden ladder, perhaps? Or something sturdier, like one made of iron? The children were eager to find a way to reconnect with the stream. Following a roundtable discussion (and after the last of the candy was gone), we decided to head back down to the village together. Before leaving, however, the children asked what to do with the stones they had collected. “You could throw them into the river!” The suggestion sparked excitement, and one by one, they hurried to the railing to make their throws. “You could come back in a few days to see how far they’ve moved,” we added, and this idea was met with joy. We like to think – and it is our responsibility to reflect on – the symbolic meaning of this action, as if saying: “Now, it’s your turn, stream ecosystem!” We hope this act planted the seeds for an ongoing, reciprocal exchange with this geo-body, which, in its own way, joins the game. Perhaps it also sets the stage for other unprecedented encounters between them, with or without us.

In conclusion, the words of the children of San Martino, their imaginative wanderings, provide us with a simple yet effective example of how we can establish a channel of communication with the stream. The turtles, the donkeys, the ladder, and the stones serve as “mediators”, keys to unlocking a new form of contact and dialogue. This does not mean we should now expect to find these fantastical creatures in the Caudino (unfortunately). Rather, Marco's perspective, along with that of the other children, invite us to see something more; they challenge us to imagine a different scenario – not salvific or catastrophic, just different.

Whether we like it or not, the stream exists, and it is up to us to recognize the opportunity to view it not merely as a “sabotaging subject” in human lives, but as a body that lives in and passes through San Martino Valle Caudina, just like its human inhabitants. Since this coexistence takes place anyway, why not open ourselves to the desire to create an alliance?

About the authors:

Lucia Ruocco is pursuing her studies in Environmental Humanities at the Department of Philosophy, Communication, and Performing Arts at Roma Tre University. She has completed degrees in Political Science from La Sapienza University in Rome and in International Relations from L’Orientale University in Naples. Her research interests encompass environmental humanities, sociology of political phenomena, social psychology, and the application of qualitative methods to economic and financial studies. She has published articles in national journals such as Dinamopress and Resetinrete and works as an independent researcher and an activist.

Sara Corrado is a researcher in performing arts. She has completed degrees in Cultural Heritage from the Gabriele D'Annunzio University of Chieti and in Visual Arts from Alma Mater Studiorum in Bologna. She is currently enrolled in the Master's program in Environmental Humanities at the Department of Philosophy, Communication, and Performing Arts at Roma Tre University. Her research focuses on performative practices related to urban crossings, understood both as an aesthetic experience of inhabited space and as a tool for investigating it. Additionally, she is involved in social and community artistic practices. Currently, she is an independent researcher and a volunteer with AICS at the Community Houses of Bologna.

Lucia Ruocco is pursuing her studies in Environmental Humanities at the Department of Philosophy, Communication, and Performing Arts at Roma Tre University. She has completed degrees in Political Science from La Sapienza University in Rome and in International Relations from L’Orientale University in Naples. Her research interests encompass environmental humanities, sociology of political phenomena, social psychology, and the application of qualitative methods to economic and financial studies. She has published articles in national journals such as Dinamopress and Resetinrete and works as an independent researcher and an activist.

Sara Corrado is a researcher in performing arts. She has completed degrees in Cultural Heritage from the Gabriele D'Annunzio University of Chieti and in Visual Arts from Alma Mater Studiorum in Bologna. She is currently enrolled in the Master's program in Environmental Humanities at the Department of Philosophy, Communication, and Performing Arts at Roma Tre University. Her research focuses on performative practices related to urban crossings, understood both as an aesthetic experience of inhabited space and as a tool for investigating it. Additionally, she is involved in social and community artistic practices. Currently, she is an independent researcher and a volunteer with AICS at the Community Houses of Bologna.

Footnotes

1 Header image: In between poisonous turtles and donkeys, by Pelatina.

2: See: https://www.master-territorio-environment.it/

3: See: https://www.master-territorio-environment.it/summer-school-motus-terrae-scuola-metarurale-2024/ From July 10 to 14, 2024 the Summer School Motus Terrae. Scuola metarurale, organized by master’s program in Environmental Humanities at Roma Tre University, worked on small territorial storytelling exercises, shared on air by setting up a radio station in the public square of San Martino Valle Caudina. The Summer School was held in conjunction with the Liminaria festival, a cultural initiative that uses art to explore new ways of observing and experiencing rural areas in Southern Italy: https://www.liminaria.org/

4: For the video of the 2019 landslide, see: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EICCpEXnVQY

5: In Italian, derivare, from Latin derivare, literally, "to draw water from a stream".

1 Header image: In between poisonous turtles and donkeys, by Pelatina.

2: See: https://www.master-territorio-environment.it/

3: See: https://www.master-territorio-environment.it/summer-school-motus-terrae-scuola-metarurale-2024/ From July 10 to 14, 2024 the Summer School Motus Terrae. Scuola metarurale, organized by master’s program in Environmental Humanities at Roma Tre University, worked on small territorial storytelling exercises, shared on air by setting up a radio station in the public square of San Martino Valle Caudina. The Summer School was held in conjunction with the Liminaria festival, a cultural initiative that uses art to explore new ways of observing and experiencing rural areas in Southern Italy: https://www.liminaria.org/

4: For the video of the 2019 landslide, see: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EICCpEXnVQY

5: In Italian, derivare, from Latin derivare, literally, "to draw water from a stream".